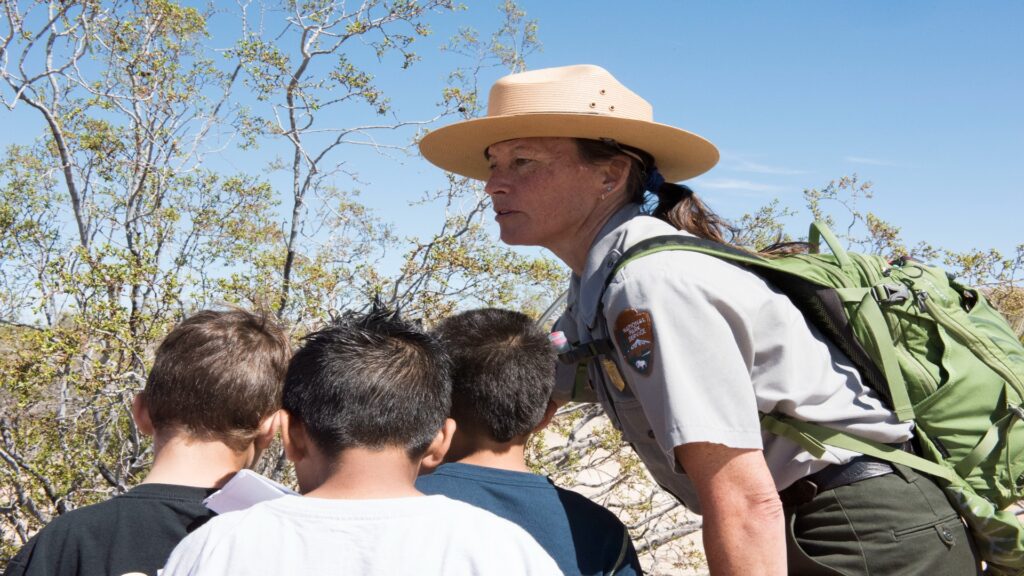

In the heart of America’s most remote and challenging wilderness areas, park rangers stand as sentinels of conservation, facing nature’s most extreme conditions with remarkable resilience. These dedicated professionals don’t just observe the wild—they live within it, navigating everything from scorching desert heat to blinding blizzards while protecting precious ecosystems and ensuring visitor safety. Their daily reality often involves conditions that would overwhelm most people, yet they persist with specialized training, equipment, and an unwavering commitment to the natural world.

This article explores the extraordinary measures park rangers take to survive and thrive in some of Earth’s most unforgiving environments, revealing the skills, strategies, and spirit that make their unique profession possible.

Extreme Temperature Management: From Desert Heat to Arctic Cold

Park rangers in places like Death Valley must function in temperatures that regularly exceed 120°F (49°C), requiring specialized hydration protocols and modified work schedules to avoid heat-related illnesses. On the opposite extreme, rangers in Alaska’s Denali National Park face winter temperatures that can plummet below -40°F (-40°C), necessitating layering techniques that allow for both insulation and ventilation while preventing dangerous sweating that could later freeze.

These professionals learn to read their bodies with exceptional precision, recognizing early warning signs of hypothermia or heat exhaustion before conditions become life-threatening. Beyond personal safety, rangers must maintain the mental clarity to make sound decisions for visitors’ safety while their bodies are under significant physiological stress from temperature extremes.

Water Sourcing and Purification in Remote Areas

Unlike typical backpackers who plan routes around known water sources, park rangers often must work in assigned areas regardless of water availability, developing advanced water sourcing skills. They become experts at identifying unlikely water sources such as rock seeps, desert springs, and plant condensation that most visitors would overlook.

Many rangers carry specialized equipment, including portable reverse osmosis systems that can make brackish or even seawater potable in coastal parks. In particularly dry environments like the Grand Canyon’s inner gorge, rangers may establish and maintain hidden water caches along patrol routes, carefully mapping and monitoring these critical resources throughout the season.

Some veteran rangers develop almost preternatural abilities to “read” landscapes for water indicators, noticing subtle vegetation changes or geological formations that suggest water might be found nearby.

Navigating Without Technology in Wilderness Settings

When GPS fails and batteries die, park rangers rely on expert map and compass skills that few modern outdoor enthusiasts fully master. Rangers develop mental maps of their territories so comprehensive they can navigate in zero-visibility conditions using terrain association—feeling elevation changes, noting vegetation transitions, and even tracking the direction of water flow underfoot.

In places like Olympic National Park’s temperate rainforest, where dense canopy can block GPS signals and persistent clouds obscure celestial navigation aids, rangers learn to pace count and use natural indicators such as moss growth patterns and prevailing wind effects on trees.

Many rangers practice regular “technology blackout” training scenarios, navigating complex routes using only analog tools to maintain these critical skills. This navigational self-sufficiency becomes particularly crucial during search and rescue operations when rangers must locate lost visitors who may have wandered off established trails.

Wildlife Encounters and Conflict Management

Park rangers develop specialized protocols for safely navigating territories shared with predators like grizzly bears, mountain lions, and wolves, learning to read animal behavior with nuance that goes far beyond typical wilderness first aid courses.

In places like Yellowstone, rangers carry bear spray and noise makers, but more importantly, they cultivate situational awareness that helps prevent dangerous encounters before they occur. They become adept at spotting subtle signs of animal stress or territorial behavior, often deescalating potential conflicts by strategic positioning and movement patterns that communicate non-threat to wildlife.

Rangers working in predator-dense areas often modify their daily routines seasonally—avoiding dawn and dusk patrols during certain times of year or adjusting routes around known den sites or feeding areas. Many rangers report developing a “sixth sense” about animal presence after years in the field, noticing changes in bird calls, insect activity, or even air scents that indicate a predator may be nearby.

Emergency Medical Care When Help Is Hours Away

Unlike urban first responders with rapid hospital access, backcountry rangers must provide extended emergency care in situations where evacuation might take 12 hours or more. Most wilderness rangers maintain Wilderness First Responder or even Wilderness EMT certifications, allowing them to perform advanced procedures rarely covered in standard first aid courses.

Rangers in remote areas frequently carry expanded medical kits, including equipment for wound irrigation, temporary tooth-filling materials, prescription-strength medications under physician protocols, and sometimes even field surgical instruments for emergency procedures.

They become skilled at improvising medical supplies from natural materials when needed—using spruce sap as an antimicrobial wound dressing or crafting splints from available vegetation. These medical skills extend beyond human care, as rangers occasionally provide emergency treatment to injured wildlife or pack animals when veterinary assistance is unavailable.

Shelter Construction and Survival Architecture

When storms arrive unexpectedly or emergencies require overnight stays in unplanned locations, rangers employ advanced shelter-building techniques adapted to specific ecosystems. In snow-heavy environments like Mount Rainier, rangers can construct snow caves and quinzhees with specialized design features that maintain safe breathing while maximizing heat retention.

Desert rangers develop techniques for creating shade structures that utilize minimal materials while providing maximum protection from the sun, often incorporating natural features like rock overhangs. Many rangers become adept at “micro-site selection,” identifying terrain features that offer natural protection from prevailing weather patterns, wildlife activity, and potential hazards like rockfall or flash flooding.

Some ranger teams maintain hidden emergency shelters throughout remote patrol areas—simple structures stocked with basic survival supplies that provide critical fallback options when conditions deteriorate rapidly.

Mental Resilience and Psychological Survival Strategies

The psychological challenges of ranger work often rival the physical ones, particularly for backcountry rangers who may work alone for weeks at a time in complete isolation. Rangers develop structured mental resilience practices, including mindfulness techniques specifically adapted for wilderness settings and cognitive strategies for managing fear during high-stress situations.

Many ranger training programs now include specific modules on recognizing and addressing the symptoms of isolation stress, compassion fatigue from frequent rescue operations, and secondary trauma from witnessing visitor injuries or fatalities. Veteran rangers often establish personal rituals and practices that help maintain psychological equilibrium—whether daily journaling, predetermined radio check-ins with colleagues, or scheduling periodic “town days” to reconnect with community.

This psychological preparedness becomes especially crucial during extended search and rescue operations when rangers must maintain clear decision-making despite physical exhaustion, emotional stress, and sometimes discouraging conditions.

Communication Systems in Areas Without Connectivity

Rangers patrolling remote backcountry where cellular and radio signals can’t penetrate develop intricate communication redundancies that most visitors never consider. Beyond standard radio systems, many units utilize satellite messengers and specialized signal-boosting equipment adapted for their specific terrain challenges.

In mountainous areas like Glacier National Park, rangers learn to identify natural features that can serve as radio relay points, sometimes hiking miles out of their way to reach a ridge or peak where transmission becomes possible. For extended backcountry assignments, some agencies employ scheduled check-in protocols with predetermined emergency responses if communications aren’t received within certain timeframes.

Rangers working in particularly remote assignments often become proficient in alternative communication methods, including mirror signaling, ground-to-air visual indicators, and, in some regions, traditional smoke signals that can convey basic emergency information across vast distances.

Fire Management in Dangerous Conditions

While many rangers partner with specialized wildfire crews, all wilderness rangers must develop basic fire management skills suitable for both emergency warming and wildfire response. Rangers learn to assess fire danger with remarkable precision, noting subtle changes in fuel moisture, wind patterns, and atmospheric conditions that might escape a casual observer’s notice.

In fire-prone regions like California’s Sierra Nevada, rangers become adept at identifying natural firebreaks and defensible spaces that could prove lifesaving during rapid fire advance. Many rangers maintain certification in wildland firefighting techniques, enabling them to properly establish backburns, fire lines, and other containment measures when initial response is needed before specialized teams arrive.

During lightning-caused ignition events, rangers may monitor multiple small fires simultaneously, making complex triage decisions about which require immediate intervention versus which can be allowed to burn under careful observation.

Specialized Equipment and Adaptive Technology

The typical ranger’s equipment combines standard outdoor gear with highly specialized tools developed for their specific operational environment. Rangers patrolling avalanche-prone areas carry expanded snow safety equipment, including specialized probes, shovels designed for emergency excavation, and sometimes personal avalanche airbag systems.

Desert rangers often utilize custom-modified vehicles with enhanced cooling systems, supplemental water storage, and shade extensions that create workable field stations in extreme heat. Many rangers in remote assignments employ solar charging systems that maintain essential electronics during extended backcountry deployments, often with custom weatherproofing modifications for their particular climate challenges.

Perhaps most impressively, rangers frequently develop their own gear innovations—creating hybrid tools, modifying standard equipment, or repurposing materials to meet the unique demands of their specific terrain and assignment.

Search and Rescue Operations in Challenging Terrain

When visitors become lost or injured, rangers must execute search and rescue operations across some of the most difficult terrain imaginable. Rangers develop specialized tracking skills that allow them to follow subtle human signs across rock, sand, and even snow—noticing compression patterns, vegetation disturbance, and micro-evidence that untrained observers would miss entirely.

In popular but dangerous areas like the Grand Canyon, rangers establish pre-planned evacuation routes with cached technical rescue equipment at strategic points, allowing rapid response to common accident locations. Many backcountry ranger stations maintain detailed records of historical search and rescue incidents, creating institutional knowledge about where lost visitors tend to make navigation errors or where terrain features create rescue challenges.

During complex rescues, rangers must often improvise technical systems using limited available equipment, sometimes creating mechanical advantage systems or improvised litters that can safely transport patients across extreme terrain.

Seasonal Adaptation and Climate Extremes

Unlike visitors who experience parks briefly during optimal conditions, rangers must adapt to the full seasonal cycle, including transitional periods that often present the most dangerous conditions. Spring rangers at high elevations navigate the hazardous “between season” when trails may be partially snow-covered and partially muddy, creating complex travel challenges and unpredictable conditions.

Rangers in parks with extreme seasonal variations like Yellowstone develop different patrol routes, equipment loadouts, and safety protocols for each season, sometimes completely reinventing their operational approach four times yearly. Coastal rangers must adjust to seasonal tidal variations that dramatically change access routes and potential hazards, sometimes rendering standard trails completely impassable during certain moon phases or seasonal current shifts.

This constant adaptation extends to physical conditioning, with many rangers following seasonal training regimens that prepare their bodies for the specific demands of each season’s typical emergencies and patrol requirements.

Knowledge Transfer and Traditional Survival Wisdom

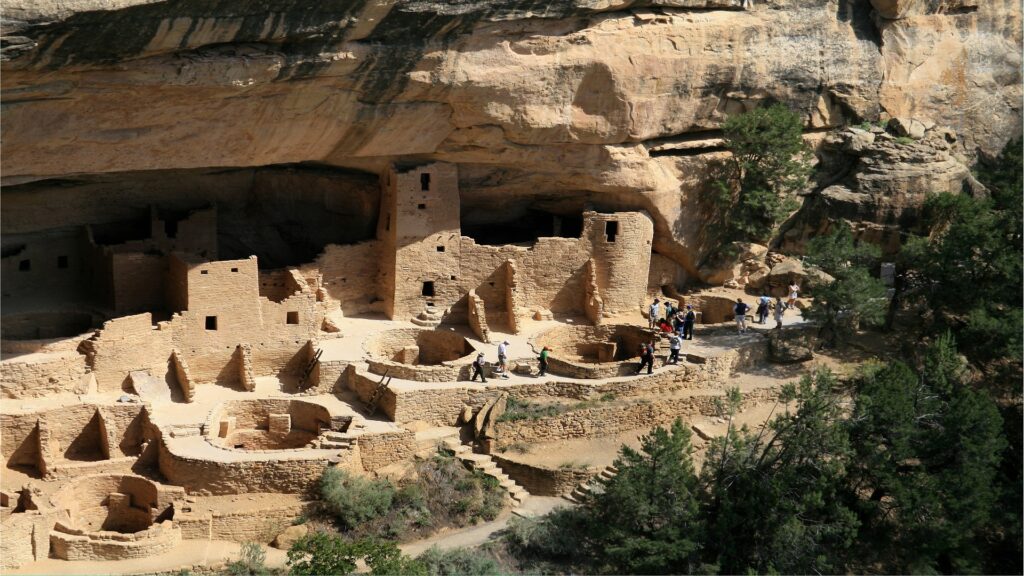

Beyond formal training, rangers benefit from rich traditions of knowledge passed down through generations of wilderness professionals and often incorporating indigenous wisdom specific to their regions. In parks like Mesa Verde or Canyon de Chelly, rangers work closely with tribal partners to learn traditional desert survival techniques that have proven effective for centuries, including native plant usage and natural water sourcing methods.

Many parks maintain “ranger wisdom books”—unofficial collections of local knowledge about area-specific challenges and solutions not covered in standard manuals or training materials. Veteran rangers frequently mentor newcomers through an informal apprenticeship system, sharing location-specific insights about microclimate patterns, seasonal hazards, and terrain quirks that might take years to discover independently.

This knowledge transfer creates an invaluable institutional memory about each park’s unique challenges, helping new rangers avoid reinventing solutions to problems their predecessors have already solved.

Conclusion

The life of a park ranger embodies an extraordinary blend of modern wilderness skills and timeless survival wisdom, all in service to protecting America’s natural treasures. These dedicated professionals combine scientific knowledge with practical fieldcraft developed through years of direct experience in some of Earth’s most challenging environments.

While visitors glimpse these wild places briefly, rangers immerse themselves fully in the rhythms and realities of wilderness living, developing profound connections to the landscapes they protect. Their remarkable adaptability and resilience don’t just ensure their own survival—they make it possible for millions of visitors to safely experience the transformative power of America’s wildest places. In an increasingly controlled and comfortable world, park rangers maintain essential knowledge about how humans can still live and work in genuine partnership with the wild.