From the comfort of their backyards to remote wilderness areas, everyday people are making extraordinary contributions to wildlife conservation. Citizen science—the practice of public participation in scientific research—has revolutionized how we monitor and understand wildlife populations across the globe. Armed with smartphones, digital cameras, and a passion for nature, volunteers of all ages and backgrounds are collecting valuable data that would be impossible for professional scientists to gather alone.

This collaborative approach has not only expanded our knowledge of species distribution and behavior but has also fostered a deeper connection between communities and their natural environments. As traditional research funding faces constraints, these citizen-powered initiatives have become increasingly vital to conservation efforts worldwide.

The Rise of Citizen Science in Wildlife Monitoring

Citizen science as a practice dates back centuries, with early naturalists often relying on observations from the public, but the digital revolution has transformed this casual participation into systematic data collection on an unprecedented scale. The advent of user-friendly mobile applications, online databases, and social media platforms has eliminated many traditional barriers to scientific participation. Projects like eBird, launched by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology in 2002, now boast millions of observations annually from birders around the world, creating one of the largest biodiversity datasets ever assembled.

This democratization of science has allowed researchers to monitor wildlife populations across vast geographic areas and time scales that would be logistically and financially prohibitive using traditional research methods alone. The growth of these programs reflects both technological advancement and a cultural shift toward more inclusive, participatory approaches to scientific discovery.

Smartphone Apps Revolutionizing Wildlife Tracking

Mobile technology has become the cornerstone of modern citizen science, with specialized apps transforming ordinary smartphones into powerful data collection tools. Applications like iNaturalist, Seek, and Wildlife Spotter enable users to document wildlife sightings with precise GPS coordinates, timestamps, and high-resolution photographs that can be instantly uploaded to global databases. Machine learning algorithms increasingly assist users with species identification, making these platforms accessible even to beginners with limited taxonomic knowledge.

The convenience of these digital tools has enabled spontaneous participation, where a chance encounter with wildlife can be documented without specialized equipment or prior planning. Many apps incorporate gamification elements like achievement badges, species checklists, and community challenges that maintain user engagement while ensuring consistent data collection across seasons and habitats.

Community-Based Wildlife Monitoring Programs

Beyond individual participation through apps, structured community monitoring programs provide frameworks for systematic wildlife observation in specific regions. These initiatives often involve training sessions where participants learn standardized protocols for data collection, species identification, and habitat assessment. The North American Breeding Bird Survey, for instance, has relied on volunteer observers since 1966 to conduct annual roadside counts along established routes, generating crucial long-term population trend data.

Similarly, the Christmas Bird Count, organized by the National Audubon Society since 1900, mobilizes thousands of volunteers each December to document winter bird populations across the Western Hemisphere. These community programs foster social connections among participants while producing consistent, comparable datasets that can detect subtle changes in wildlife populations over time.

Camera Traps and Volunteer Photo Analysis

Remote camera technology has revolutionized wildlife monitoring by capturing images of elusive, nocturnal, or dangerous species with minimal human disturbance. While professional researchers deploy many of these camera traps, citizen scientists increasingly participate by installing cameras on their own properties or analyzing the millions of images these devices generate. Projects like Snapshot Serengeti, Zooniverse’s WildCam Gorongosa, and Snapshot Wisconsin involve volunteers in classifying animals captured in camera trap images through user-friendly online platforms.

These initiatives have processed millions of images that would overwhelm professional research teams, identifying animals that might otherwise go undetected in remote or challenging environments. The visual nature of camera trap data also makes these projects particularly engaging for volunteers, who experience the thrill of discovering rare or charismatic species in their natural habitats.

Tracking Migrations and Animal Movements

Understanding animal movements across landscapes is crucial for conservation planning, yet tracking migratory species presents enormous logistical challenges that citizen scientists help overcome. Projects like Monarch Watch engage thousands of volunteers in tagging monarch butterflies to document their remarkable multi-generational migration between Mexico and Canada. Journey North allows participants to report first sightings of migratory species each spring, creating continental-scale maps of migration timing that reveal responses to changing climate conditions.

Marine wildlife tracking programs like Whale Alert and Shark Spotters enable beachgoers and boaters to report sightings that help protect vulnerable species in coastal waters. These collaborative efforts not only generate valuable scientific data but also create emotional connections between participants and the remarkable journeys of migratory animals.

Monitoring Urban Wildlife

As urbanization accelerates globally, understanding how wildlife adapts to human-dominated landscapes has become increasingly important, with citizen scientists perfectly positioned to document these interactions. Urban wildlife programs like Chicago’s Coyote Project, Toronto’s Wild Urban Spaces, and London’s Garden Wildlife Health project engage city residents in reporting wildlife sightings, behaviors, and health issues observed in metropolitan areas. These initiatives reveal surprising adaptations as species like peregrine falcons, coyotes, and raccoons adjust their behaviors to thrive in cities, sometimes reaching higher densities than in their natural habitats.

Urban citizen science programs often uncover important human-wildlife conflict zones that benefit from targeted management interventions. The accessibility of urban monitoring programs makes them ideal entry points for diverse participants who might not otherwise engage with nature conservation.

Marine and Coastal Wildlife Monitoring

Oceans cover more than 70 percent of Earth’s surface, making professional monitoring of marine wildlife particularly challenging, yet coastal communities worldwide are helping fill these knowledge gaps through citizen science. Initiatives like REEF’s Fish Survey Project train recreational divers and snorkelers to conduct standardized fish counts that have documented shifting species distributions across tropical and temperate reefs. Beachcombing projects like CoastWatch and the Marine Debris Monitoring Program engage shoreline visitors in documenting stranded wildlife, nesting activities, and pollution impacts.

Whale watching tours increasingly double as research platforms, with passengers helping to photograph and identify individual whales for long-term population studies. These marine citizen science projects not only generate valuable data but also build ocean literacy and conservation advocacy among coastal communities.

Contributions to Rare Species Conservation

For rare and endangered species, citizen scientists serve as crucial early warning systems, often detecting population changes or new threats before they appear in formal monitoring programs. The California Roadkill Observation System allows drivers to report wildlife collisions, identifying mortality hotspots that inform wildlife crossing construction to protect vulnerable species.

Australia’s FrogID program enables participants to record frog calls, helping track declining amphibian populations across the continent while discovering previously unknown populations of threatened species. Volunteer reptile monitoring programs have documented range expansions of endangered turtles and identified new breeding sites requiring protection.

For species with extremely limited ranges, local citizen scientists often become the primary guardians, developing intimate knowledge of population dynamics that complements the periodic assessments of professional biologists.

Tracking Invasive Species Spread

Invasive species represent one of the greatest threats to biodiversity worldwide, with citizen scientists forming critical detection networks that help contain their spread. Early detection is crucial for successful management, and distributed networks of trained volunteers can identify and report invasive species far more efficiently than limited professional monitoring teams.

Programs like EDDMapS (Early Detection and Distribution Mapping System) and IveGot1 enable participants to photograph and report invasive plants and animals, creating real-time distribution maps that guide rapid response efforts. The Lionfish Derby series in the Caribbean trains recreational divers to safely remove invasive lionfish from coral reefs while collecting data on their abundance and size distribution.

These citizen-powered early warning systems have proven particularly valuable for aquatic invasives like zebra mussels and Asian carp, where prompt detection can prevent establishment in vulnerable watersheds.

Quality Control and Data Validation

As citizen science data increasingly informs conservation decisions and scientific publications, ensuring data quality has become a central focus of program design. Modern citizen science platforms incorporate multiple validation mechanisms, including expert review, community verification, and automated filters that flag unusual observations for additional scrutiny.

Most established programs provide standardized protocols, identification guides, and training sessions that minimize observer error and ensure consistent methodology. Applications like iNaturalist employ a tiered verification system where observations start as “needs ID” before community members and taxonomic experts confirm identifications.

Statistical approaches can also identify and correct for observer bias, allowing researchers to confidently incorporate citizen-collected data into analyses while accounting for variation in participant skill levels. These quality control measures have helped citizen science data gain acceptance in peer-reviewed scientific literature and conservation policy decisions.

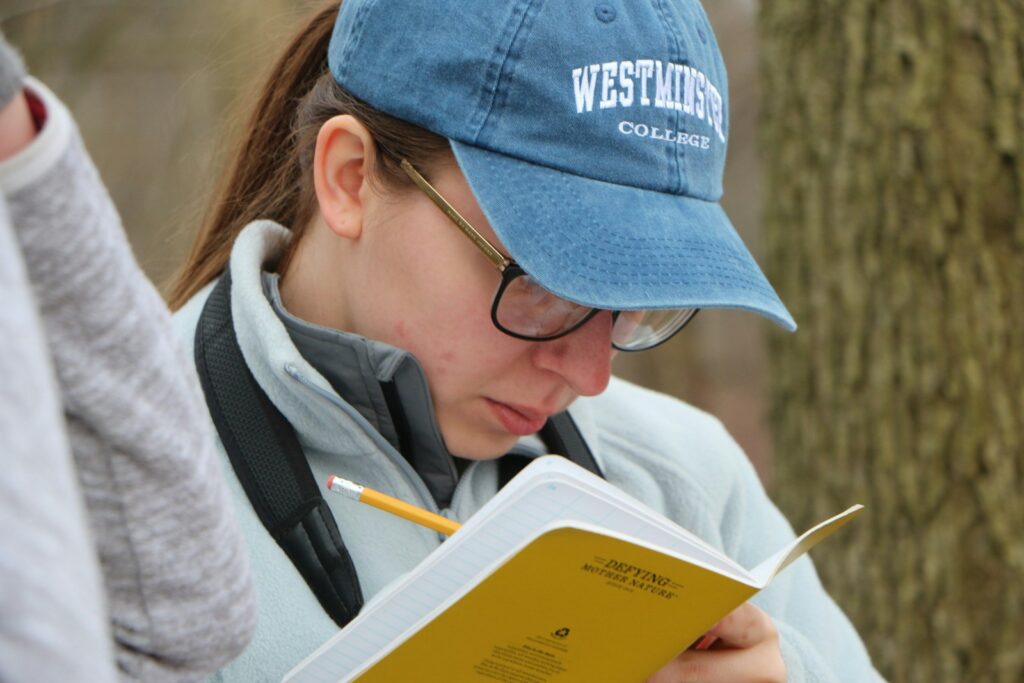

Educational and Community Benefits

Beyond scientific contributions, wildlife citizen science delivers profound educational and social benefits to participating communities. Research shows that regular participation in nature observation increases ecological knowledge, scientific literacy, and conservation ethics among diverse participants.

Schools increasingly incorporate citizen science into curriculum, providing authentic science experiences that develop data collection skills while fostering deeper connections to local ecosystems. Community-based monitoring programs strengthen social bonds between participants who share common interests and contribute to collective environmental goals.

Indigenous and traditional communities bring valuable ecological knowledge to citizen science programs, creating cross-cultural learning opportunities while ensuring their perspectives inform conservation decisions. For many participants, especially in urban areas, wildlife monitoring provides a structured entry point to nature observation that develops into lifelong environmental stewardship.

The Future of Citizen Wildlife Monitoring

As technology evolves and public participation expands, citizen science approaches to wildlife monitoring continue to develop in exciting new directions. Emerging technologies like acoustic monitoring devices, environmental DNA sampling, and drone surveys are becoming increasingly accessible to trained volunteers, expanding the types of data citizen scientists can collect.

Artificial intelligence tools are enhancing species identification capabilities, allowing participants to contribute valuable data even without extensive taxonomic expertise. New analytical approaches are improving integration between professional and citizen datasets, creating comprehensive monitoring systems that leverage the strengths of both approaches.

International coordination between citizen science programs is increasing, enabling tracking of wide-ranging species across political boundaries and creating standardized protocols that allow data comparison between regions. As these innovations continue, citizen scientists will play an increasingly central role in understanding and protecting global biodiversity.

How to Get Involved in Wildlife Citizen Science

For those inspired to contribute to wildlife monitoring, numerous entry points exist regardless of experience level or location. Beginning participants can download wildlife observation apps like iNaturalist, Merlin Bird ID, or Seek, which provide identification assistance and connect observations to global databases with minimal commitment.

Regional conservation organizations typically offer local monitoring opportunities focused on specific habitats or species of concern in your area. National initiatives like the Audubon Christmas Bird Count, FrogWatch USA, and NestWatch welcome participants annually with structured protocols and training materials available online.

For those seeking more immersive experiences, many wildlife research organizations offer volunteer field positions assisting with surveys, tagging, or habitat assessments. Even backyard observations can contribute valuable data through projects like Project FeederWatch, the Great Backyard Bird Count, or Garden Wildlife Health, making wildlife citizen science accessible to nearly everyone with an interest in nature.

Conclusion: Connecting People and Nature Through Citizen Science

Citizen science has transformed wildlife monitoring from an activity restricted to professional biologists into a global movement engaging millions of volunteers. This democratization of science has expanded our collective understanding of biodiversity while building stronger connections between people and the natural world.

As environmental challenges intensify with climate change, habitat loss, and species decline, the eyes and ears of citizen scientists provide invaluable early warning systems and monitoring capacity that would be impossible to achieve through professional efforts alone. The movement continues to evolve, becoming more inclusive, technologically sophisticated, and scientifically rigorous—ensuring that ordinary people will remain extraordinary partners in wildlife conservation for generations to come.