The creation of national parks represents one of humanity’s most forward-thinking conservation achievements. These protected landscapes—from towering mountain ranges to sprawling deserts and ancient forests—stand as living monuments to our collective commitment to preserve natural wonders. But how exactly were these specific areas chosen for protection? The process of selecting lands worthy of national park designation has evolved dramatically over time, reflecting changing values, scientific understanding, and cultural priorities. What began as an effort to protect scenic wonders has transformed into a sophisticated system balancing biodiversity conservation, cultural heritage preservation, recreational opportunities, and ecological significance. This article explores the fascinating evolution of how national parks were selected, from the earliest designations to the complex, multi-faceted approaches used today.

The Birth of an Idea: Yellowstone and Early Visions

The concept of national parks emerged in the United States during the late 19th century, culminating with Yellowstone’s designation as the world’s first national park in 1872. This groundbreaking designation didn’t follow a formal selection process as we understand it today—rather, it stemmed from the reports of early explorers like the Washburn-Langford-Doane Expedition, whose members were struck by the area’s unique geothermal features and spectacular landscapes. The legend of the “campfire discussion,” where expedition members supposedly conceived the idea of preserving Yellowstone for public benefit rather than private profit, may be somewhat mythologized, but it captures the essential shift in thinking that made park creation possible. Early advocates emphasized Yellowstone’s curiosities and natural wonders, focusing primarily on scenic beauty and unique geological features rather than ecological considerations. This pattern of selecting dramatic, picturesque landscapes would dominate early park selection for decades to come.

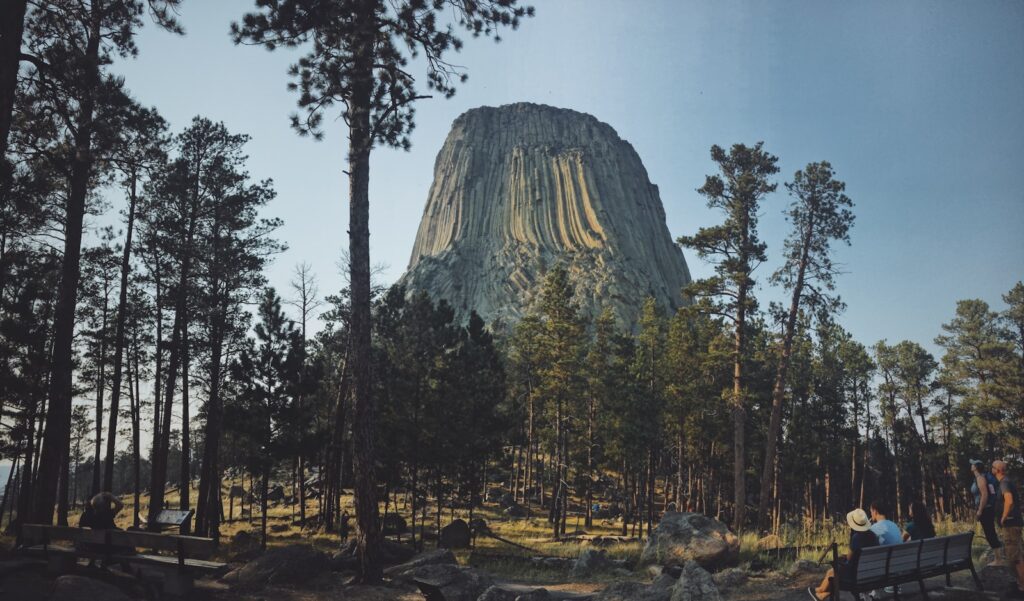

Monumental Landscapes: The Scenic Selection Era

Following Yellowstone’s designation, the selection of national parks throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries heavily favored landscapes of monumental scale and dramatic beauty. Areas like Yosemite, Grand Canyon, and Mount Rainier exemplified this approach—places where nature had created spectacular vistas that inspired awe and wonder. The selection criteria during this period were largely aesthetic and experiential, prioritizing areas that offered visitors overwhelming natural grandeur. Railroad companies played a significant role in this era of park selection, advocating for designations that would attract tourists to their lines. The Northern Pacific Railroad’s lobbying for Yellowstone’s protection and the Santa Fe Railroad’s promotion of the Grand Canyon demonstrate how commercial interests sometimes aligned with conservation goals. This era established the template of national parks as “America’s best idea”—preserving scenic wonders that could compete with Europe’s cultural monuments as symbols of national identity and pride.

Scientific Criteria Emerge: Ecological Significance

The early 20th century witnessed a gradual shift in how potential national parks were evaluated, with growing emphasis on scientific and ecological values. The establishment of the National Park Service in 1916 provided institutional support for more systematic approaches to park selection. Wildlife biologist George Wright’s pioneering studies in the 1920s and 1930s introduced biological surveys as tools for identifying areas worthy of protection. Everglades National Park, established in 1934, marked a watershed moment as the first national park selected primarily for its biological rather than scenic values—preserving a vital ecosystem rather than a spectacular landscape. This period saw the beginning of ecosystem-based thinking in park selection, with scientists arguing that representative examples of America’s diverse ecological systems deserved protection. The shift reflected growing scientific understanding of ecology and the recognition that biodiversity conservation required protecting more than just picturesque mountains and canyons.

Cultural and Historical Significance

As selection criteria evolved, cultural and historical significance became increasingly important factors in determining which areas warranted national park status. The Antiquities Act of 1906 provided a legal mechanism for protecting areas of historical and scientific interest, with many sites initially protected as national monuments later converted to national parks. Mesa Verde National Park, designated in 1906 to protect ancient Puebloan cliff dwellings, exemplified this new dimension of park selection based on cultural heritage. Historical parks commemorating key events in American history, from Revolutionary War battlefields to Civil Rights movement sites, expanded the concept of what deserved national protection. Indigenous cultural landscapes gained recognition, acknowledging that many seemingly “natural” areas had been shaped by thousands of years of native management. This broader conception of significance enabled the protection of places that told crucial stories about human interaction with the land throughout history.

Political Realities: The Role of Advocacy

The selection of national parks has never been a purely scientific or aesthetic exercise—political advocacy has always played a crucial role in determining which lands receive protection. Powerful advocates, from John Muir’s passionate defense of Yosemite to the modern environmental movement’s campaigns for Alaskan wilderness protection, have shaped the national park system through strategic lobbying and public education. The creation of Redwood National Park in the 1960s demonstrated how citizen activism could overcome commercial opposition, with a grassroots campaign successfully advocating for the protection of ancient forests threatened by logging. Congressional politics inevitably influence park selection, with representatives championing designations in their districts and states. Presidential priorities also matter enormously—Theodore Roosevelt’s conservation agenda created five national parks and 18 national monuments, while Jimmy Carter’s Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act protected over 100 million acres in a single legislative act. These political dimensions remind us that park selection reflects not just objective criteria but also values, power dynamics, and effective advocacy.

Geographic Distribution and Representation

As the national park system matured, increasing attention focused on ensuring geographic distribution and representation of diverse American landscapes. Early park selections concentrated heavily in the western states, where vast public lands and spectacular scenery made designations easier. The National Park Service eventually recognized the need to protect representative examples of ecological regions throughout the country, not just in the dramatic landscapes of the West. The establishment of eastern parks like Shenandoah, Great Smoky Mountains, and Acadia in the 1920s and 1930s partially addressed this geographic imbalance. Systematic approaches to identifying gaps in representation developed over time, with park planners analyzing the country’s ecological regions to identify unrepresented areas worthy of protection. This attention to representation continues today, with advocates identifying ecosystem types still lacking adequate protection within the national park system.

Scientific Assessment and Gap Analysis

Modern approaches to national park selection rely heavily on sophisticated scientific assessment and gap analysis techniques. Conservation biologists conduct systematic surveys to identify areas of exceptional biodiversity, rare habitats, or critical importance for endangered species. Geographic Information Systems (GIS) allow planners to analyze multiple factors simultaneously, from species richness to ecosystem connectivity and climate change resilience. The gap analysis process systematically identifies ecosystems underrepresented in the current protected areas network, prioritizing these for future conservation action. Organizations like NatureServe work with government agencies to map biodiversity hotspots and assess conservation status, providing data-driven frameworks for selection decisions. These scientific approaches ensure that limited conservation resources target areas of maximum biological significance, moving well beyond the earlier focus on scenic grandeur alone.

International Models and Standards

The selection of protected areas has increasingly been influenced by international models and standards developed through global conservation initiatives. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) established protected area categories that help standardize approaches to selection and management across countries. World Heritage Site designation through UNESCO provides additional recognition for parks with outstanding universal value, encouraging the protection of globally significant landscapes. International treaties like the Convention on Biological Diversity establish targets for protected area coverage, influencing national policies on park creation. American national park selection has both influenced and been influenced by these international frameworks, creating a global conversation about what deserves protection. Transboundary parks, where protected areas cross international borders, represent an emerging approach recognizing that ecological systems don’t conform to political boundaries.

Land Availability and Opportunity

Practical considerations of land availability and opportunity have always shaped national park selection, sometimes overriding more systematic approaches. Many national parks were established on lands already in federal ownership, making designation politically and economically feasible. Declining extractive industries sometimes created openings for conservation, as seen when former timber lands became Redwood National Park or when military bases were converted to parks like Saguaro and Channel Islands. Private philanthropy has occasionally enabled park creation through strategic land donations, as when John D. Rockefeller Jr. purchased and donated lands that became critical parts of Grand Teton and Acadia National Parks. Opportunistic approaches remain important today, with conservation organizations like The Trust for Public Land or The Conservation Fund acquiring strategic properties during narrow windows of availability, then transferring them to federal protection. These pragmatic considerations remind us that ideal selection criteria must often bend to practical realities of what lands can actually be protected.

Local Community Perspectives

The role of local communities in park selection has evolved dramatically over time, from early models that often ignored or displaced residents to modern approaches that emphasize engagement and co-management. Indigenous peoples were frequently removed from lands designated as parks, a tragic history now recognized as both unjust and counterproductive for conservation goals. Recent decades have seen increasing recognition that local support is crucial for effective protection, with community input becoming a standard part of the selection process. Areas like Cuyahoga Valley National Park in Ohio exemplify community-driven designation, where local advocacy built momentum for protecting a landscape of local significance. International models like biosphere reserves specifically designate buffer zones where sustainable human use continues alongside core protected areas. These evolving approaches recognize that parks exist within social and economic contexts, and selection processes work best when they incorporate local knowledge and address community needs.

Economic Considerations

Economic factors have influenced national park selection in complex ways throughout history. Early park advocates often argued that lands had greater economic value as tourist destinations than as sites for extractive industries—a utilitarian argument that lands were “worthless except for scenery.” Tourism potential remains an important consideration in park selection, with economic impact studies documenting how protected areas can stimulate regional economies through visitor spending. Conversely, opposition to park designation often centers on concerns about lost revenue from activities like mining, logging, or development, creating political barriers to protection. Modern economic analyses incorporate ecosystem services valuation, recognizing the economic benefits of intact ecosystems for clean water, flood control, carbon sequestration, and other services. These economic dimensions highlight that park selection involves weighing different types of value, from immediate resource extraction to long-term ecological and recreational benefits.

Climate Change Resilience

The newest dimension in national park selection involves assessing areas for their resilience in the face of climate change. Conservation planners now evaluate potential protected areas not just for their current ecological value but for their likely ability to maintain biodiversity as climate patterns shift. Selection increasingly prioritizes climate refugia—areas projected to maintain relatively stable conditions despite regional climate changes due to factors like topographic diversity or stable water sources. Connectivity between protected areas has become a crucial consideration, creating corridors that allow species to migrate as conditions change. Areas with high topographic and climatic diversity receive special attention because they provide microclimates that allow species to adapt by moving short distances to find suitable conditions. These forward-looking approaches represent a significant evolution from earlier selection methods, acknowledging that protected areas must be chosen not just for what they are today but for their capacity to nurture biodiversity through coming centuries of environmental change.

Modern Integrated Approaches

Contemporary national park selection typically employs integrated approaches combining multiple criteria and stakeholder perspectives. The creation of Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument in 2016 (a potential stepping stone to national park status) exemplifies this comprehensive approach, incorporating ecological assessment, cultural significance, recreational opportunities, local economic benefits, and private conservation philanthropy. Systematic conservation planning methodologies help identify areas that simultaneously satisfy multiple objectives, from biodiversity protection to cultural heritage preservation and climate resilience. Public engagement processes have become increasingly sophisticated, with extensive consultation periods gathering input from diverse stakeholders. Collaborative governance models increasingly involve shared management between federal agencies, local communities, and indigenous peoples. These integrated approaches recognize that successful protection requires addressing ecological, cultural, economic, and social dimensions simultaneously, moving well beyond the singular focus on scenic wonders that characterized early park selection.

Conclusion

The evolution of how national parks are chosen reflects our deepening understanding of what makes landscapes valuable and worthy of protection. From the early focus on spectacular scenery to today’s sophisticated assessments of biodiversity, cultural significance, community needs, and climate resilience, selection criteria have continually expanded to embrace more holistic conceptions of value. This evolution hasn’t always been smooth—politics, economic pressures, and changing social priorities have created a system with both remarkable achievements and notable gaps. Yet the overall trajectory shows a growing recognition that protected areas serve multiple purposes, from preserving ecological systems to honoring cultural heritage, providing recreational opportunities, and building climate resilience. As we face unprecedented environmental challenges in the coming decades, these selection approaches will continue to evolve, guiding the protection of lands that future generations will treasure as we treasure our current national parks today.