The vast, untamed wilderness of America’s national parks has long captivated the imagination of filmmakers seeking breathtaking backdrops for their stories. These natural wonders, with their dramatic landscapes and pristine beauty, provide the perfect canvas for cinematic masterpieces. When Hollywood directors choose these locations, they not only enhance their films with authentic natural grandeur but also inadvertently become powerful marketing tools for the parks themselves. The relationship between national parks and cinema has created a fascinating cultural phenomenon where fictional narratives boost real-world tourism, conservation awareness, and public appreciation for these protected lands. From towering sequoias to desert mesas, canyon vistas to alpine meadows, the silver screen has transformed already beautiful destinations into legendary landmarks that viewers around the world yearn to experience firsthand.

Monument Valley: The Iconic Western Backdrop

Monument Valley, located within the Navajo Nation on the Arizona-Utah border, became synonymous with the American West through legendary director John Ford’s westerns starring John Wayne. Films like “Stagecoach” (1939) and “The Searchers” (1956) immortalized the valley’s distinctive sandstone buttes and mesas, creating an enduring visual shorthand for the frontier spirit. Though technically not a national park but tribal land, Monument Valley’s fame through cinema drove massive tourist interest, eventually leading to the creation of Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park to manage visitation and preserve the landscape. Today, visitors can take guided tours along the same routes where Ford positioned his cameras, experiencing firsthand how these natural formations became characters themselves in defining an entire film genre. The economic impact of film tourism has been substantial for the Navajo Nation, providing jobs and cultural awareness while creating a continuous dialogue about land management and indigenous rights.

Yosemite National Park’s Silver Screen Legacy

Yosemite’s majestic granite cliffs, thundering waterfalls, and ancient sequoias have featured prominently in numerous films, most notably “The Last of the Mohicans” (1992) and parts of “Star Trek V: The Final Frontier” (1989). The park’s iconic Half Dome and El Capitan formations are instantly recognizable worldwide thanks to their cinematic exposure, drawing millions of visitors annually hoping to stand where famous scenes were filmed. In 2018, the documentary “Free Solo” chronicled Alex Honnold’s death-defying climb up El Capitan without ropes, bringing international attention to the park’s rock-climbing culture and winning an Academy Award in the process. Yosemite’s film appearances date back to the silent era, with early conservationists recognizing the power of moving images to inspire protection of these natural wonders. The park has also figured prominently in countless commercials and television productions, cementing its status as the quintessential American wilderness destination in the global imagination.

Arches National Park and Indiana Jones

The opening sequence of “Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade” (1989) features a young Indiana Jones, played by River Phoenix, on a Boy Scout adventure in Utah’s breathtaking Arches National Park. The film showcases Double Arch, a spectacular natural formation where two arches share the same foundation, creating an unforgettable visual setting for Indy’s origin story. After the film’s release, park rangers reported a significant increase in visitors explicitly asking to see the “Indiana Jones arch,” demonstrating cinema’s powerful ability to create location-specific tourism. Beyond the Indiana Jones franchise, Arches has appeared in numerous science fiction films seeking otherworldly landscapes, with its red rock formations serving as stand-ins for alien planets. The delicate sandstone arches, formed over millions of years by erosion, now face conservation challenges partially due to increased foot traffic from film-inspired tourism, creating a complex relationship between preservation and the publicity that helps fund protection efforts.

Planet of the Apes and Lake Powell

The original “Planet of the Apes” (1968) used the stark, otherworldly shorelines of Lake Powell within Glen Canyon National Recreation Area to represent a post-apocalyptic Earth where apes ruled over humans. The famous final scene revealing a half-buried Statue of Liberty was filmed at nearby Lake Powell, creating one of cinema’s most shocking twist endings. This massive reservoir, created by the controversial Glen Canyon Dam, continues to attract filmmakers seeking alien-like landscapes with its unique combination of deep blue waters against red sandstone formations. Following the film’s success, tourism to Lake Powell increased dramatically, with boat tours specifically highlighting filming locations from the movie and its sequels. The recreation area now balances film production permits with conservation concerns, as decades of visitors inspired by movie imagery have created both economic opportunities and environmental challenges for the region.

Jurassic Park and Kauai’s Na Pali Coast

When Steven Spielberg needed a prehistoric paradise for “Jurassic Park” (1993), he turned to Hawaii’s dramatic Na Pali Coast on Kauai, now protected within Na Pali Coast State Wilderness Park. The film’s opening helicopter sequence showcases the verdant valleys, towering waterfalls, and rugged cliffs of this spectacular coastline, creating an instantly believable habitat for dinosaurs. The famous “Jurassic gates” scene was filmed at nearby Allerton Garden, while several key dinosaur encounters were shot in Kauai’s lush interior forests. After the blockbuster’s release, tourism to Kauai surged dramatically, with helicopter tours specifically advertising “Jurassic Park experiences” becoming a multimillion-dollar industry. The franchise’s continuing success, including the recent “Jurassic World” films which returned to film on location, ensures a steady stream of film tourists eager to experience these prehistoric landscapes. Ironically, the island’s actual prehistoric history, including unique endemic species and geological formations, often becomes secondary to visitors’ desire to recreate movie moments.

Grand Canyon as Hollywood’s Natural Wonder

The Grand Canyon’s immense scale and dramatic vistas have appeared in countless films, with its first major role in the 1991 film “Thelma & Louise,” where the iconic finale shows the protagonists driving off the canyon’s edge rather than surrendering to authorities. This particular scene, though filmed at Dead Horse Point State Park in Utah rather than the actual Grand Canyon, nevertheless drove significant tourist interest in experiencing the real canyon’s overwhelming majesty. The Grand Canyon’s South Rim viewpoints have served as backdrops for emotional revelations in films ranging from “National Lampoon’s Vacation” (1983) to “Into the Wild” (2007), cementing the location as cinema’s go-to symbol for natural awe and perspective. The canyon’s appearance in “Grand Canyon” (1991) specifically explored how encounters with such overwhelming natural wonders can provide perspective on human problems, a theme that park rangers report many visitors reference when describing their motivations for visiting. The national park has carefully managed filming permits to balance production needs with visitor experiences, recognizing both the promotional value and potential disruption that major productions can bring.

The Shining and Glacier National Park

Though the interior scenes of Stanley Kubrick’s psychological horror masterpiece “The Shining” (1980) were filmed on soundstages, the iconic opening sequence follows Jack Nicholson’s character driving along the Going-to-the-Sun Road in Glacier National Park. These sweeping aerial shots of his yellow Volkswagen winding through Montana’s rugged mountain terrain establish the film’s growing sense of isolation and dread. While the fictional Overlook Hotel was based on Colorado’s Stanley Hotel, Glacier’s dramatic landscapes provided the perfect visual foundation for the story’s remote setting and psychological desolation. After the film’s release and subsequent cult status, Glacier National Park began seeing visitors specifically seeking to recreate that famous drive, camera in hand, hoping to capture the same foreboding beauty Kubrick immortalized. Park officials have noted that fall visitation increased specifically among film enthusiasts seeking the same golden larches and empty roadways seen in the movie, extending the tourist season and creating economic benefits for local communities beyond traditional summer months.

Zabriskie Point and Death Valley

Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni’s counterculture film “Zabriskie Point” (1970) not only took its name from a famous viewpoint in Death Valley National Park but used the location’s alien badlands for some of cinema’s most visually striking scenes. The film’s climactic explosion sequence, where consumer goods blow up in slow motion against the park’s barren landscape, created an unforgettable visual metaphor for rejecting materialism. Though commercially unsuccessful upon release, the film has gained cult status among cinephiles who make pilgrimages to the actual Zabriskie Point to experience its otherworldly beauty firsthand. Death Valley’s extreme environments, including the lowest point in North America and some of the hottest recorded temperatures on Earth, have since appeared in numerous science fiction films as stand-ins for alien planets. The park’s vast salt flats, sand dunes, and colorful mineral deposits continue to attract filmmakers seeking landscapes that feel removed from ordinary human experience, creating a continuous cycle of cinematic exposure that drives tourism to one of America’s most challenging natural environments.

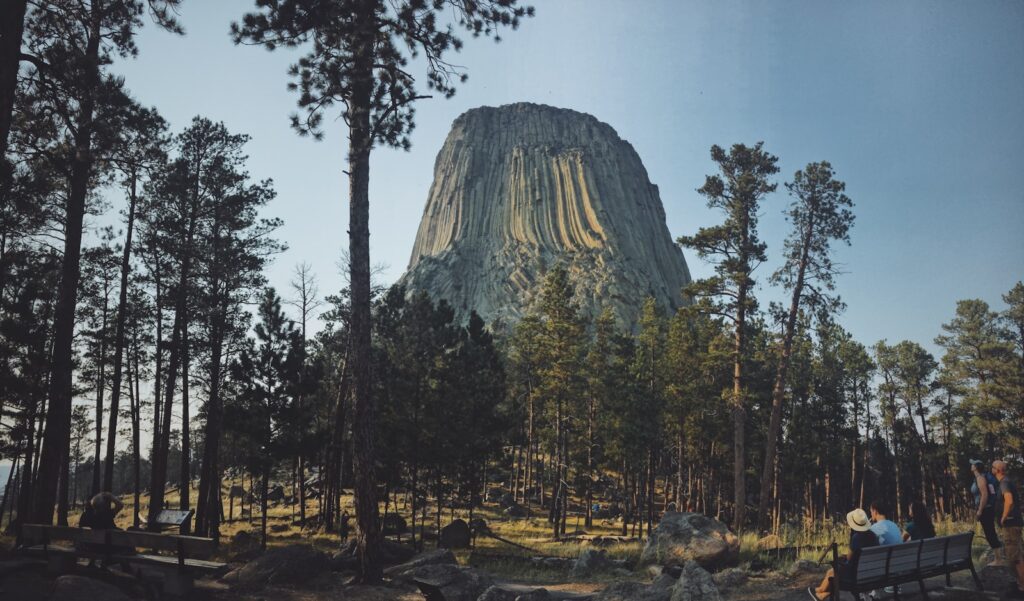

Close Encounters and Devils Tower

Steven Spielberg’s “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” (1977) transformed Devils Tower National Monument in Wyoming from a geological curiosity known primarily to rock climbers into an international tourism destination. The film used the distinctive volcanic formation as the rendezvous point for alien contact, with Richard Dreyfuss’s character becoming obsessively drawn to its unique shape. Following the film’s success, visitation to Devils Tower increased by over 75% almost immediately, with rangers reporting countless visitors recreating the famous mashed potato sculpting scene from the movie. The monument’s visitor center eventually created exhibits explaining both the scientific reality of the tower’s formation and its cinematic legacy, acknowledging how thoroughly the film had become intertwined with public perception of the site. The Native American tribes who consider Devils Tower sacred (known to them as Bear Lodge) have had to navigate the complexities of increased tourism driven by science fiction rather than cultural appreciation, highlighting the sometimes problematic aspects of Hollywood fame for protected places with deep spiritual significance.

Forrest Gump’s Impact on Multiple Parks

The 1994 Oscar-winning film “Forrest Gump” notably incorporated several national parks, with perhaps the most famous being the scene where Forrest decides to stop running at Monument Valley on the Arizona-Utah border. His cross-country running journey also featured shots from Glacier National Park, the Lincoln Memorial reflecting pool in Washington, D.C., and breathtaking views of the Mississippi River. The film’s use of these iconic American landscapes helped establish Forrest’s journey as a tour through the heart of America, both geographically and culturally. Within months of the film’s release, park rangers at Monument Valley began reporting visitors attempting to recreate the famous running scene where Forrest announces, “I’m pretty tired—I think I’ll go home now.” The film created such an enduring connection to the location that the specific spot is now informally marked and known to tour guides as “Forrest Gump Point,” despite being on U.S. Highway 163 rather than inside the tribal park itself. This single fictional moment continues drawing photography enthusiasts and film tourists more than 25 years after the movie’s release, demonstrating cinema’s lasting power to create pilgrimage sites out of previously anonymous landscapes.

The Redwoods and Return of the Jedi

The forest moon of Endor in “Star Wars: Return of the Jedi” (1983) was primarily filmed in California’s Redwood National and State Parks, bringing worldwide attention to these ancient forests with trees towering over 350 feet tall. The famous speeder bike chase sequence, where Imperial troops and rebels zip between massive tree trunks, highlighted the enormous scale of these coast redwoods while creating one of the film’s most memorable action scenes. Following the film’s release, park visitation increased substantially, with international visitors especially citing Star Wars as their inspiration for making the journey to northern California. Dedicated fans continue to seek out specific filming locations, though fallen trees and natural forest changes over decades have altered many recognizable spots from the movie. The parks now embrace this cinematic heritage while using visitor interest as an opportunity to educate about the redwoods’ ecological importance and conservation challenges, including climate change threats to these ancient forests. The partnership between Lucasfilm and the park service demonstrated how respectful filming could occur in sensitive environments while creating lasting publicity that helps build public support for conservation.

The Conservation Impact of Film Tourism

When national parks become movie stars, they often experience what park managers call the “Hollywood effect”—significant increases in visitation following a film’s release that can last for decades. This phenomenon creates complex conservation challenges as parks must balance the positive aspects of increased public interest and funding with potential negative impacts from overcrowding and resource damage. Research has shown that films create emotional connections to landscapes that translate into stronger conservation support, with viewers more likely to donate to protection efforts for places they recognize from beloved movies. Parks featured in films typically see 20-40% increases in visitation in the years following release, with certain iconic locations experiencing even larger surges that require adaptive management strategies. The National Park Service has developed sophisticated film permit processes that ensure productions minimize environmental impacts while maximizing promotional benefits, recognizing cinema’s unique power to create new conservation advocates. Many parks now incorporate film history into their interpretive programs, using visitors’ cinematic familiarity as an entry point for deeper environmental education about the real ecological and cultural significance beyond the movie moments.

Digital Effects vs. Authentic Locations

As CGI technology advances, filmmakers increasingly face the choice between filming in actual national parks or creating digital environments that mimic their distinctive features. Many directors still insist on authentic locations, arguing that the tangible qualities of real landscapes inspire better performances and create more emotionally resonant viewing experiences. Park managers have observed that even in the digital age, films using actual locations generate more tourism than those using computer-generated backdrops, suggesting audiences can sense authentic connection to place even through the screen. Studios must weigh the logistical challenges and permit restrictions of filming in protected areas against the marketing value of advertising “filmed on location” in iconic destinations. This ongoing tension has created interesting hybrid approaches, where brief establishing shots in real parks are combined with studio work and digital extensions, allowing films to maintain authentic connections to these landscapes while minimizing on-site disruption. As virtual production technology improves, parks are developing new strategies to maintain beneficial relationships with the entertainment industry while protecting their resources from the physical impacts of large-scale productions.

From John Ford’s westerns to modern blockbusters, America’s national parks have provided some of cinema’s most unforgettable backdrops while receiving invaluable exposure in return. This symbiotic relationship between conservation and entertainment continues to evolve as filmmakers find new ways to showcase these natural treasures and park managers develop strategies to handle the resulting fame. For many visitors, standing in locations they recognize from favorite films creates powerful moments of connection—not just to the movies, but to the landscapes themselves. As we increasingly experience nature through screens, these cinematic introductions to national parks may become even more crucial in inspiring new generations to protect these irreplaceable places. The stories may be fictional, but the impact on conservation awareness and appreciation for natural wonders is very real, making Hollywood an unlikely but effective partner in the ongoing effort to preserve America’s most spectacular landscapes.