America’s national parks stand today as symbols of natural preservation and foresight, drawing millions of visitors annually to experience their pristine beauty. Yet the existence of these protected treasures was far from guaranteed. Before attaining their protected status, many of America’s most beloved national parks faced imminent threats from commercial exploitation, development projects, and resource extraction that could have permanently altered their landscapes. The path from vulnerable natural wonder to federally protected parkland often involved bitter conflicts between conservationists and commercial interests, with the fate of some of America’s most spectacular landscapes hanging in the balance. This article explores the precarious histories of several national parks that narrowly escaped destruction before receiving the protections they enjoy today.

Yosemite Valley: The Struggle Against Private Exploitation

Before becoming part of Yosemite National Park, the spectacular valley faced numerous threats from private commercial interests in the late 19th century. Entrepreneurs claimed land in the valley, building hotels and sawmills and even establishing private toll roads to profit from early tourists. James Mason Hutchings, who published some of the first articles about Yosemite, claimed 160 acres in the valley and operated a hotel while vigorously fighting government attempts to protect the area. Sheep grazing—what conservationist John Muir called “hoofed locusts”—was degrading the valley’s meadows, while logging threatened the surrounding forests. These growing threats prompted conservationists led by Muir to campaign for protection, eventually resulting in the Yosemite Grant of 1864, which ceded the valley to California as protected land, though it would take decades more of struggle before comprehensive protections were established with the creation of Yosemite National Park in 1890.

Hetch Hetchy Valley: The Park Battle That Was Lost

Perhaps the most heartbreaking conservation loss in national park history occurred within Yosemite itself. Hetch Hetchy Valley, often described as a “twin” to the more famous Yosemite Valley, was dammed and flooded in the early 20th century despite being within the boundaries of Yosemite National Park. Following the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, city officials sought a reliable water source and identified Hetch Hetchy as an ideal reservoir site. This sparked what many consider America’s first major national environmental controversy, with conservationist John Muir and the Sierra Club battling against the dam for years. Despite Muir’s passionate plea that “dam Hetch Hetchy! As well as dams for water tanks, the people’s cathedrals and churches,” Congress passed the Raker Act in 1913, allowing the valley to be dammed. The O’Shaughnessy Dam was completed in 1923, submerging the valley under 300 feet of water, creating a lasting reminder that even national park designation doesn’t guarantee permanent protection.

Grand Canyon: Mining Claims and Development Threats

The Grand Canyon, now considered among the world’s most awe-inspiring natural wonders, faced serious threats from mining, tourism development, and even hydroelectric dams before receiving adequate protection. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, thousands of mining claims were staked throughout the canyon, with prospectors extracting copper, asbestos, and uranium from its depths. Railroad companies proposed extensive development along the rim, including large hotel complexes that would have fundamentally altered the natural viewshed. Among the most audacious threats was a proposal to dam the Colorado River within the canyon, which would have flooded significant portions of this natural wonder. President Theodore Roosevelt, who first visited in 1903, recognized these dangers and initially protected the area as a game preserve and later as a national monument in 1908, declaring, “Leave it as it is. You cannot improve on it.” Despite this, it would take until 1919 for the area to receive full national park status, following years of battles with mining and development interests.

Yellowstone: Saving America’s First National Park

Before becoming the world’s first national park in 1872, Yellowstone faced threats that could have dramatically altered its unique landscape. Early expeditions to the region, including the Washburn-Langford-Doane Expedition of 1870, documented discussions around campfires about how participants might profit from Yellowstone’s wonders by claiming land around key attractions. Railroad interests sought to build lines directly to thermal features, while poachers decimated wildlife populations, bringing bison to near extinction and severely reducing elk and antelope numbers. Vandalism was another significant concern, with early visitors chipping away at fragile geyser formations for souvenirs and carving names into thermal features. The Northern Pacific Railroad, while eventually supporting park designation, did so primarily because they saw tourism potential for their lines, highlighting how economic considerations often shaped conservation outcomes. Even after park designation, Yellowstone suffered from inadequate protection until the U.S. Army was assigned to patrol the park in 1886, finally providing meaningful oversight against exploitation.

Olympic National Park: Logging the “Million Dollar Tree”

The old-growth temperate rainforests of Olympic National Park were once viewed primarily as a timber resource to be harvested rather than a unique ecosystem to be preserved. In the early 20th century, logging companies rapidly cut through the peninsula’s ancient forests, with some individual trees valued at over a million dollars in today’s currency due to their massive size and high-quality wood. The forest was being cleared at such an alarming rate that conservationists feared the entire ecosystem would be lost within decades. President Grover Cleveland designated the Olympic Forest Reserve in 1897, but this did little to stop logging since forest reserves allowed for “wise use” of resources. Even after President Theodore Roosevelt established Mount Olympus National Monument in 1909 to protect the Roosevelt elk habitat, timber interests successfully lobbied to reduce its size by nearly half in 1915, opening more forest to logging. The forest continued to face threats until 1938, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt, after flying over the peninsula and seeing the extent of clear-cutting, signed legislation establishing Olympic National Park.

Glacier National Park: Mining and Resource Extraction

The spectacular mountains of Glacier National Park were once viewed primarily through the lens of potential mineral wealth rather than natural beauty. Prospectors flocked to the region in the late 19th century after the discovery of copper and gold deposits, establishing mining claims throughout what would later become the park. The Great Northern Railway, while eventually supporting conservation, initially saw the area as a source of timber and minerals to support their operations. Oil exploration threatened the eastern regions of the future park, with drilling operations established that could have expanded significantly without protective intervention. Water development projects, including proposed dams on several major lakes and rivers, would have transformed the park’s natural hydrology and scenic character had they been implemented. The protection of Glacier came about through an unusual alliance between Louis Hill of the Great Northern Railway, who recognized the tourism potential, and conservationists like George Bird Grinnell, resulting in the park’s establishment in 1910, though this didn’t immediately end all extraction activities within its boundaries.

Everglades National Park: Draining the “Worthless Swamp”

Florida’s Everglades were long considered a worthless swampland to be “reclaimed” through drainage for agriculture and development. In the early 20th century, Florida governor Napoleon Bonaparte Broward campaigned on a promise to drain the Everglades, declaring, “Water will run downhill,” as drainage canals and levees were constructed to convert wetlands to farmland and urban development. These drainage efforts dramatically altered water flow patterns, with devastating ecological consequences as wildlife populations declined and saltwater intrusion became problematic. Real estate speculation drove further development pressure, with advertisements promoting drained Everglades land as an agricultural paradise. The sugar industry established massive operations on drained land, creating a powerful economic interest that continues to influence Everglades water management today. Conservation efforts led by figures like Marjory Stoneman Douglas, who famously described the Everglades as a “river of grass” rather than a swamp, eventually led to the establishment of Everglades National Park in 1947, though by then much of the original ecosystem had already been irrevocably altered.

Grand Teton National Park: The Secret Land Acquisition

The dramatic Teton Range and the valley at its feet faced significant development pressure before becoming fully protected as Grand Teton National Park. Although the mountains themselves received protection in 1929, the critical valley floor remained in private ownership, with rapidly expanding ranches, tourist accommodations, and commercial developments threatening to transform the landscape. John D. Rockefeller Jr., after visiting in 1926 and seeing the commercial development spreading across the valley, began secretly purchasing land through the Snake River Land Company with the intention of donating it to the park. When his plan became public, it faced fierce opposition from local residents and Wyoming politicians who objected to federal control of the land, with the controversy lasting for decades. Despite death threats and burning effigies, Rockefeller persisted in his conservation effort, eventually acquiring approximately 35,000 acres at a cost of $1.4 million (equivalent to over $25 million today). After years of political resistance, President Franklin Roosevelt finally established Jackson Hole National Monument in 1943 to protect the Rockefeller lands, which were later incorporated into an expanded Grand Teton National Park in 1950.

Redwood National Park: Saving the Last Ancient Giants

By the time conservation efforts began for California’s coast redwoods, nearly 90% of the original ancient forests had already been logged. Timber companies were rapidly harvesting the remaining old-growth redwoods, some of which had been growing for over 2,000 years, with little concern for their irreplaceable nature or ecological importance. The creation of Redwood National Park in 1968 protected only a small fraction of the remaining old-growth forest, leaving significant stands vulnerable on private lands adjacent to the park. Particularly problematic was the practice of clear-cutting on steep hillsides above park boundaries, causing massive erosion that damaged protected redwood groves downstream. The timber industry vigorously opposed park expansion, arguing that jobs would be lost and local economies devastated if logging was restricted. After a contentious battle between conservationists and timber interests, Congress finally approved a significant expansion of the park in 1978, adding 48,000 acres that included critical watershed areas necessary to protect the ancient trees. The Redwood experience demonstrated that protecting just the trees themselves wasn’t enough—entire ecosystems needed protection to ensure the survival of these ancient forests.

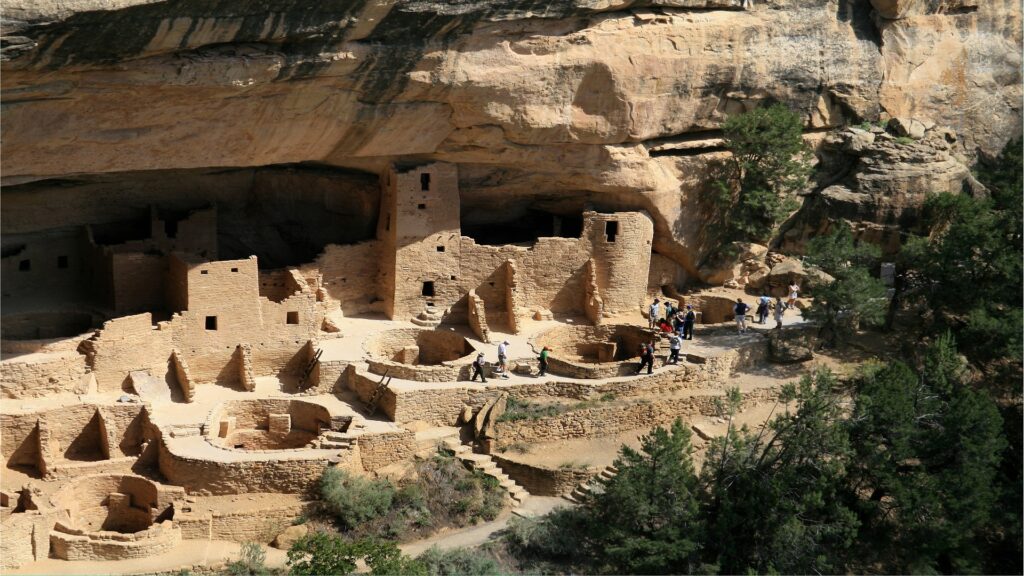

Mesa Verde: Looting America’s Archaeological Treasures

The extraordinary cliff dwellings of Mesa Verde faced a different kind of threat—systematic looting and vandalism of irreplaceable archaeological resources. After their rediscovery by cowboys in the late 19th century, the ancient Puebloan ruins became targets for pot hunters and souvenir seekers who removed countless artifacts, damaged structures, and even used dynamite to expose hidden chambers. Museums and collectors around the world paid handsomely for Mesa Verde artifacts, creating a lucrative market that encouraged continued destruction of sites. Local rancher and amateur archaeologist Richard Wetherill conducted some of the earliest explorations of the ruins, removing numerous artifacts that were sold to institutions like the American Museum of Natural History, though his methods would be considered extremely destructive by modern archaeological standards. Archaeological photographer and journalist Virginia McClurg initially campaigned to protect the sites, though controversially she later advocated for private rather than federal control. The tireless advocacy of Swedish-American archaeologist Gustaf Nordenskiöld, who published some of the first scientific studies of the ruins, and later the determined efforts of Lucy Peabody, eventually led to Mesa Verde’s designation as a national park in 1906, specifically to protect its archaeological treasures rather than natural features.

Acadia: When the Wealthy Saved Nature from the Wealthy

The stunning coastal landscape of Maine’s Mount Desert Island, now protected as Acadia National Park, was rapidly being transformed into a playground for the ultra-wealthy during the Gilded Age. By the early 20th century, massive summer “cottages”—in reality elaborate mansions—were being constructed along prime coastal properties, while developers envisioned exclusive resorts and private estates that would have severely limited public access to the island’s natural beauty. In an unusual twist of conservation history, it was primarily wealthy summer residents themselves who became concerned about this trend and took action to protect the island. Harvard president Charles W. Eliot and George B. Dorr, both summer residents, formed the Hancock County Trustees of Public Reservations in 1901 to acquire and preserve land for public use. Financier John D. Rockefeller Jr. joined the effort, donating more than 11,000 acres and funding the construction of the park’s distinctive carriage roads. Their efforts led to the establishment of Sieur de Monts National Monument in 1916, which was redesignated Lafayette National Park in 1919 (and later renamed Acadia in 1929), becoming the first national park east of the Mississippi River and a rare example of conservation driven by private philanthropy rather than government initiative.

The Contemporary Conservation Challenge: Gateway Communities and Climate Change

Even today’s established national parks face ongoing threats that could fundamentally alter their character and ecological integrity. Gateway communities adjacent to popular parks have experienced explosive growth and development, with places like Gatlinburg (Great Smoky Mountains), West Yellowstone, and Springdale (Zion) transforming from small towns into tourism hubs with hotels, attractions, and services that generate light pollution, noise, and visual impacts affecting park experiences. Climate change represents perhaps the most significant contemporary threat, with rising temperatures causing glacial retreat in parks like Glacier and North Cascades, while altered precipitation patterns affect water-dependent ecosystems in parks from Everglades to Yosemite. Increased visitation, which reached record levels in many parks following the COVID-19 pandemic, has created management challenges related to infrastructure capacity, wildlife disturbance, and degradation of natural resources. The emergence of new recreational technologies like drones, e-bikes, and backcountry motorized vehicles has created regulatory challenges unforeseen by early park planners. These contemporary threats demonstrate that even established national parks require constant vigilance and adaptive management to ensure their preservation for future generations.

The Ongoing Battle for America’s Public Lands

The threats that once faced our now-protected national parks continue to endanger other public lands across America. Proposals for resource extraction regularly target lands adjacent to national parks, with recent controversies including oil drilling near Theodore Roosevelt National Park and mining operations proposed near Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness. Grand Staircase-Escalante and Bears Ears National Monuments in Utah became flashpoints in public land debates when their boundaries were dramatically reduced in 2017, allowing for potential resource extraction in previously protected areas, though these reductions were reversed in 2021. The establishment of new protected areas frequently faces intense opposition from resource industries and some local communities concerned about economic impacts, following a pattern established over a century ago. Funding challenges remain a persistent issue, with the National Park Service facing a maintenance backlog exceeding $22 billion, compromising its ability to adequately protect resources and manage visitation. The continuing struggle to protect America’s natural and cultural heritage demonstrates that conservation is never permanently won but requires ongoing commitment from each new generation to ensure these irreplaceable treasures are preserved.

Conclusion

The story of America’s national parks is as much about what could have been lost as what was saved. Each of these iconic landscapes faced serious threats before receiving protection—some narrowly escaping permanent alteration, others bearing lasting scars from early exploitation. The preservation of these natural treasures didn’t happen accidentally or inevitably but required dedicated individuals willing to fight powerful commercial interests and short-term thinking. From John Muir’s eloquent defense of Yosemite to the Rockefellers’ strategic land acquisitions, conservation victories came through passionate advocacy and visionary action. As we enjoy these protected landscapes today, their histories remind us that even our most treasured natural places once stood on the brink of destruction, highlighting the continuing need for vigilance in protecting America’s natural heritage for future generations.