America’s national parks serve as sanctuaries for natural wonders, preserving breathtaking landscapes for future generations. Yet hidden within these protected wildernesses lie forgotten human stories—abandoned towns, homesteads, and communities that once thrived before the land gained federal protection. These ghost settlements offer haunting glimpses into America’s past, where pioneers, miners, farmers, and indigenous peoples once built lives amid what are now protected ecosystems. From crumbling cabins in the Great Smoky Mountains to deserted mining operations in Death Valley, these abandoned places tell tales of boom-and-bust economies, natural disasters, government displacement, and changing ways of life. As nature slowly reclaims these human imprints, park visitors can explore these atmospheric ruins and contemplate the complex relationship between human history and wilderness preservation.

The Creation of National Parks and Displacement of Communities

The establishment of America’s national parks, while celebrated for wilderness preservation, often came at a significant human cost. When the National Park Service began designating protected areas in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, numerous communities already occupied these lands—some for generations. Federal acquisition of these territories frequently meant forced relocation of residents, with varying degrees of compensation and often little regard for cultural attachments to place. In Shenandoah National Park, for instance, hundreds of mountain families were displaced in the 1930s, with their homes, schools, and churches abandoned to the elements. Similarly, the creation of Great Smoky Mountains National Park resulted in the removal of over 1,200 small landowners, though some elderly residents received special permits to remain on their land until death. These displacements represent an often overlooked chapter in conservation history—the human sacrifice behind America’s “pristine” wilderness areas.

Mining Ghost Towns: Boom and Bust Cycles Preserved

Throughout American national parks, abandoned mining settlements stand as testament to the volatile boom-and-bust cycles that once drove frontier expansion. Perhaps nowhere is this more evident than in Death Valley National Park, where the ghost town of Rhyolite once boasted 10,000 residents during a gold rush that lasted just a few short years from 1905-1911. Today, visitors can explore its crumbling bank building, railroad depot, and the famous bottle house constructed of discarded beer and liquor bottles. In Colorado’s Rocky Mountain National Park, the remains of Lulu City represent a silver boom town that flourished briefly in the 1880s before economic collapse prompted its abandonment. These mining settlements often featured hastily constructed buildings, elaborate social establishments like saloons and dance halls, and primitive extraction equipment—all now slowly deteriorating under the forces of nature and time. What makes these sites particularly haunting is how quickly they transformed from bustling centers of human ambition to silent ruins, capturing the transient nature of frontier economic ventures.

Lost Agricultural Communities in the Cuyahoga Valley

Ohio’s Cuyahoga Valley National Park harbors a unique collection of abandoned farm settlements that tell the story of America’s changing agricultural landscape. Throughout the park, visitors encounter historic farmhouses, weathered barns, and overgrown fields that once sustained thriving family farms dating back to the early 19th century. The Countryside Initiative program within the park has documented over 75 historic agricultural structures, many abandoned when the federal government began acquiring valley properties in the 1970s. Unlike many national parks established in remote wilderness areas, Cuyahoga Valley developed amid an already settled landscape, leading to a different pattern of abandonment as farming became economically unsustainable for many families. The iconic Everett Road Covered Bridge stands near former farmsteads, while the preserved Hale Farm and Village offers a glimpse of how these communities once functioned. These agricultural ruins represent not sudden abandonment but gradual decline, as America transitioned from family farming to industrial agriculture throughout the 20th century.

Elkmont: The Ghost Resort Town of the Smokies

Deep within Great Smoky Mountains National Park lies Elkmont, perhaps the most atmospheric abandoned settlement in the entire national park system. Originally established as a logging camp in the early 1900s, Elkmont transformed into an exclusive vacation community when wealthy families from Knoxville constructed rustic seasonal homes along the Little River. After the park’s creation in the 1930s, residents received lifetime leases to continue using their cabins, creating a peculiar situation where a private resort community existed within national park boundaries for decades. As these leases finally expired in the 1990s and 2000s, the National Park Service gained control of approximately 70 historic structures, many in advanced states of decay. The “Daisy Town” section of Elkmont has been partially preserved, with several cabins stabilized to showcase the distinctive Appalachian resort architecture. Walking Elkmont’s quiet streets today, visitors experience a powerful sense of suspended time—rocking chairs still sit on sagging porches, vintage wallpaper peels from interior walls, and stone chimneys stand sentinel as nature gradually reclaims this once-vibrant social hub of Tennessee’s elite.

Indigenous Settlements and the Complicated History of Park Creation

National parks across America contain significant archaeological remains of indigenous settlements that represent a particularly complex chapter in the history of abandoned places within protected lands. In Mesa Verde National Park, the spectacular cliff dwellings of Ancestral Puebloan people were abandoned centuries before European contact, presenting a different type of “ghost settlement” that became central to the park’s creation and identity. However, many other parks have more troubling histories, where native communities were actively displaced during park establishment. When Glacier National Park was created in 1910, the Blackfeet people lost access to traditional hunting and gathering grounds central to their cultural identity and survival. Similarly, the establishment of Yosemite required the removal of indigenous Miwok and Paiute people who had inhabited the valley for thousands of years. Throughout the system, visitors encounter the stone foundations, artifact scatters, and sacred sites of native peoples—some abandoned naturally through migration patterns, others forcibly emptied through government policies. These indigenous settlement remains add crucial perspective to understanding the full human history of lands now managed primarily for natural values.

Island Communities Lost to Time: Channel Islands National Park

The remote Channel Islands off California’s coast preserve some of the most isolated abandoned settlements within the national park system, where maritime communities once struggled to build lives amid challenging ocean conditions. On Santa Cruz Island, the remains of Scorpion Ranch stand as testament to generations of sheep ranchers who established a self-sufficient ranching operation beginning in the 1850s. Visitors today can explore the preserved adobe ranch house, blacksmith shop, and various outbuildings that supported this isolated enterprise until its abandonment in the mid-20th century. On nearby Santa Rosa Island, the historic Vail & Vickers Ranch operated for over 150 years until the National Park Service acquired the property in the 1980s. These island settlements faced unique challenges—everything from building materials to medical care required dangerous boat journeys to the mainland, while limited freshwater and harsh maritime weather constantly threatened survival. The preservation of these island communities offers rare insight into the extraordinary adaptations required for humans to inhabit such isolated environments before modern transportation and communication.

Vanished Logging Camps of Olympic National Park

Within Washington’s Olympic National Park, the forgotten remnants of once-bustling logging camps bear witness to the timber industry that dramatically reshaped the Pacific Northwest before conservation efforts halted commercial logging. Throughout the park’s valleys and lowland forests, hikers occasionally stumble upon rusting equipment, rotting spar trees, and the deteriorating foundations of bunkhouses where loggers lived in primitive conditions. The abandoned settlement at Elwha tells a particularly compelling story, where a small community supported the operations of a massive dam constructed in 1913 to power timber mills. When the Olympic National Park boundaries were established in 1938, many logging operations became enclosed within protected wilderness, their equipment too heavy to remove economically. These abandoned sites represent a pivotal moment in American conservation history, when the nation began to question unrestrained resource extraction after witnessing the devastation of once-magnificent forests. Today, as massive trees slowly reclaim these former clear-cuts, the abandoned logging infrastructure stands as both environmental cautionary tale and testament to the incredible human effort once devoted to harvesting the Northwest’s timber resources.

Threatened by Water: Drowned Towns in National Recreation Areas

Some of the most haunting abandoned settlements within the National Park System lie hidden beneath the waters of man-made reservoirs, occasionally revealing themselves during drought conditions. At Lake Mead National Recreation Area, the town of St. Thomas, Nevada emerged from the waters in 2002 after decades of submersion, exposing building foundations, rusting vehicle parts, and other remnants of a Mormon settlement established in 1865. The town was gradually abandoned between 1936 and 1938 as the rising waters of the newly constructed Hoover Dam inundated the community despite residents’ protests. Similarly, Cades Cove in Great Smoky Mountains National Park was slated for flooding during proposed dam projects in the 1930s, though conservation efforts ultimately spared it from becoming another underwater ghost town. These drowned settlements represent a particularly emotional type of abandonment, where residents often fought to save communities with deep historical roots, only to watch them disappear beneath reservoir waters. During exceptional drought years, the reappearance of these towns creates a powerful visual metaphor for the human cost of water management and development policies throughout America’s history.

Preservation Challenges: Saving Ruins While Maintaining Wilderness

The National Park Service faces significant philosophical and practical challenges in managing abandoned settlements within park boundaries, balancing historic preservation against wilderness management mandates. The Organic Act that established the agency requires protection of both natural and cultural resources “unimpaired for future generations,” creating inherent tensions when deciding the fate of deteriorating structures. At Elkmont in Great Smoky Mountains National Park, decades of debate ensued before officials determined which cabins merited preservation and which would be removed to restore natural conditions. The remote location of many abandoned settlements creates additional preservation difficulties—transporting building materials to stabilize a historic mining cabin in Denali’s backcountry, for instance, requires expensive helicopter operations that strain limited budgets. Climate change further complicates preservation efforts, as increasing wildfire intensity, more frequent flooding, and accelerated decay threaten fragile historic resources. Park managers must continually evaluate which abandoned structures tell essential stories worth preserving and which might be documented and then allowed to deteriorate naturally as part of the wilderness experience, recognizing that not every historic structure can or should be saved indefinitely.

Abandoned Military Installations within Park Boundaries

Throughout the national park system, abandoned military installations stand as powerful reminders of America’s defensive history, often presenting unique preservation challenges due to their size and complexity. At Gulf Islands National Seashore, the massive fortress of Fort Pickens represents one of the largest brick structures in the United States, abandoned by the military after nearly a century of active use from the 1830s through World War II. In Golden Gate National Recreation Area, visitors explore the atmospheric remains of Fort Cronkhite, a WWII coastal defense installation with concrete bunkers built to defend San Francisco from Japanese attack. Hawaii’s USS Arizona Memorial at Pearl Harbor commemorates the most somber type of military abandonment—a battleship that became a tomb for 1,177 sailors and Marines. These military ruins differ from other abandoned settlements in scale and purpose, often featuring massive concrete structures designed specifically for defensive purposes rather than community life. Their presence in national parks creates interpretive opportunities to discuss America’s military history within the context of places now dedicated to peace and natural preservation, highlighting the sometimes jarring juxtaposition between warfare and conservation.

Paranormal Reputation: Ghost Stories from Abandoned Park Settlements

The atmospheric abandoned settlements within national parks have inevitably attracted numerous paranormal legends, with rangers and visitors reporting unexplained experiences that add another dimension to these historic places. In Great Smoky Mountains National Park, the Norton Creek area near Cataloochee has generated persistent stories of a phantom Appalachian homesteader appearing near abandoned cabin sites, supposedly representing a resident who refused to leave when the government acquired the land. Death Valley’s abandoned Scotty’s Castle has inspired tales of mysterious piano music and the apparition of its eccentric former owner, Walter Scott, still wandering his desert mansion. The abandoned mining town of Rhyolite features prominently in Nevada ghost hunting lore, with visitors reporting disembodied voices in the ruins of the former bank building. While the National Park Service typically focuses interpretation on factual history rather than supernatural claims, many park rangers acknowledge these ghost stories as part of the cultural narrative surrounding these evocative places. The prevalence of such legends speaks to the powerful emotional response these abandoned places evoke—the sense that something of their former inhabitants lingers in the deteriorating structures and lonely landscapes they left behind.

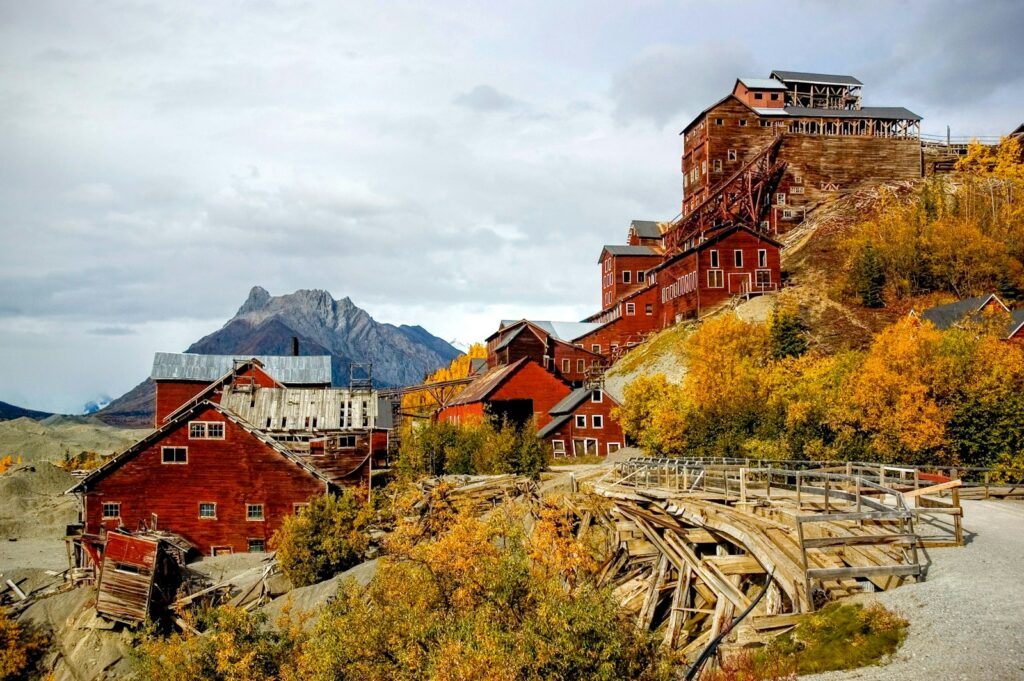

Ethical Tourism: Respecting Abandoned Places When Visiting

For modern visitors exploring abandoned settlements in national parks, significant ethical considerations apply to ensure these fragile historical resources remain protected for future generations. The National Park Service explicitly prohibits removing artifacts or disturbing ruins, following the preservation principle of “take only photographs, leave only footprints.” Even seemingly insignificant items like rusted nails or fragments of household goods provide important archaeological context that helps historians understand daily life in these vanished communities. When visiting places like the abandoned mining town of Kennecott in Alaska’s Wrangell-St. Elias National Park, tourists should remain on designated pathways to prevent further deterioration of structures that may be unstable after decades of abandonment. Many parks also request that visitors avoid posting specific GPS coordinates of lesser-known ruins on social media to prevent overcrowding at sensitive archaeological sites. Beyond legal requirements, ethical visitation involves contemplating the human stories connected to these places—acknowledging that many represent communities displaced through government action, economic hardship, or environmental challenges. Approaching abandoned settlements with respect and historical awareness transforms tourism from mere ruin photography into meaningful engagement with America’s complex past.

Future of Forgotten Places: Climate Change and Preservation Planning

The abandoned settlements within America’s national parks face an uncertain future as climate change accelerates deterioration and forces difficult preservation decisions. Rising sea levels directly threaten coastal ruins like those on Cumberland Island National Seashore, where the remains of plantation-era structures may be inundated within decades. Increasing wildfire frequency and intensity endanger wooden structures in western parks, with several historic mining cabins in Sequoia National Park already lost to recent catastrophic fires. Park managers have begun implementing climate vulnerability assessments for cultural resources, prioritizing documentation of threatened sites and developing triage protocols for which structures merit expensive stabilization efforts. Some parks employ innovative preservation techniques, such as 3D laser scanning at Chaco Culture National Historical Park, creating detailed digital records of ancestral Puebloan structures that may eventually succumb to climate impacts. The future likely involves difficult decisions about managed retreat—acknowledging that not all historic structures can be saved indefinitely in their original locations. As these abandoned places continue their slow return to nature, accelerated by changing climate conditions, their documentation and interpretation become increasingly vital to preserving the stories of those who once called these now-protected landscapes home.

As we explore the abandoned settlements scattered throughout America’s national parks, we encounter a profound paradox: the very act of wilderness preservation has inadvertently preserved these haunting human imprints. These ghost towns, homesteads, and vanished communities offer more than just atmospheric photography opportunities—they provide essential perspective on our complex relationship with the land. They remind us that these “wild” places have long histories of human habitation and use, challenging simplistic views of pristine nature untouched by humanity. From displaced indigenous communities to boom-and-bust mining operations, from flooded towns to abandoned military installations, these silent ruins speak eloquently about American dreams, failures, and changing values concerning the landscape. As climate change and natural deterioration increasingly threaten these fragile historical resources, our responsibility to document, understand, and respectfully visit them becomes ever more important. The forgotten settlements of our national parks stand as powerful reminders that wilderness and human history are inseparably intertwined.