Beneath the majestic landscapes of America’s national parks lies a hidden world seldom seen by casual visitors. While millions admire the towering redwoods, cascading waterfalls, and sweeping vistas above ground, a remarkable subterranean realm of caves, tunnels, and underground wonders tells an equally compelling story of our nation’s geological heritage. From massive cathedral-like caverns adorned with delicate formations to tight passages leading to underground lakes and rivers, these hidden spaces represent some of the most pristine and scientifically valuable environments in the park system.

These underground realms not only showcase extraordinary beauty but also serve as time capsules, preserving evidence of ancient climates, extinct species, and geological processes spanning millions of years.

The Remarkable History of Cave Exploration in National Parks

The story of cave exploration in America’s national parks is filled with colorful characters, remarkable discoveries, and occasionally tragic outcomes. In the early days, intrepid explorers ventured into these mysterious underground spaces with little more than candles or oil lamps, mapping passages and documenting features with rudimentary tools. Mammoth Cave in Kentucky, now recognized as the world’s longest known cave system with over 400 miles of surveyed passages, saw its first documented explorations by enslaved guides like Stephen Bishop in the early 19th century.

Wind Cave National Park in South Dakota was discovered in 1881 when brothers Tom and Jesse Bingham heard a whistling sound coming from a small hole in the ground—the pressure difference between the cave and surface creating the distinctive wind that gave the cave its name. These pioneering explorers laid the groundwork for cave science and conservation, eventually leading to the protection of these underground treasures within the national park system.

Mammoth Cave: The Crown Jewel of Underground National Parks

Mammoth Cave National Park in Kentucky protects the most extensive known cave system on Earth, with more than 400 miles of surveyed passageways—and experts believe much more remains to be discovered. The cave’s vast chambers include the aptly named Grand Avenue, which stretches for miles beneath the surface, and the breathtaking Frozen Niagara formation, a massive flowstone resembling a petrified waterfall. Beyond its impressive size, Mammoth Cave harbors a remarkable diversity of unusual life forms, including several species of eyeless fish and crayfish that have evolved to thrive in perpetual darkness.

The human history of Mammoth Cave is equally fascinating, from prehistoric Native American explorers who ventured miles into the cave 4,000 years ago to leave behind artifacts, to the 19th-century mining of cave saltpeter used to manufacture gunpowder during the War of 1812. Today, the park offers a variety of guided tours allowing visitors to experience different sections of this underground wilderness while protecting its delicate ecosystems.

Carlsbad Caverns: A Subterranean Wonderland in the Desert

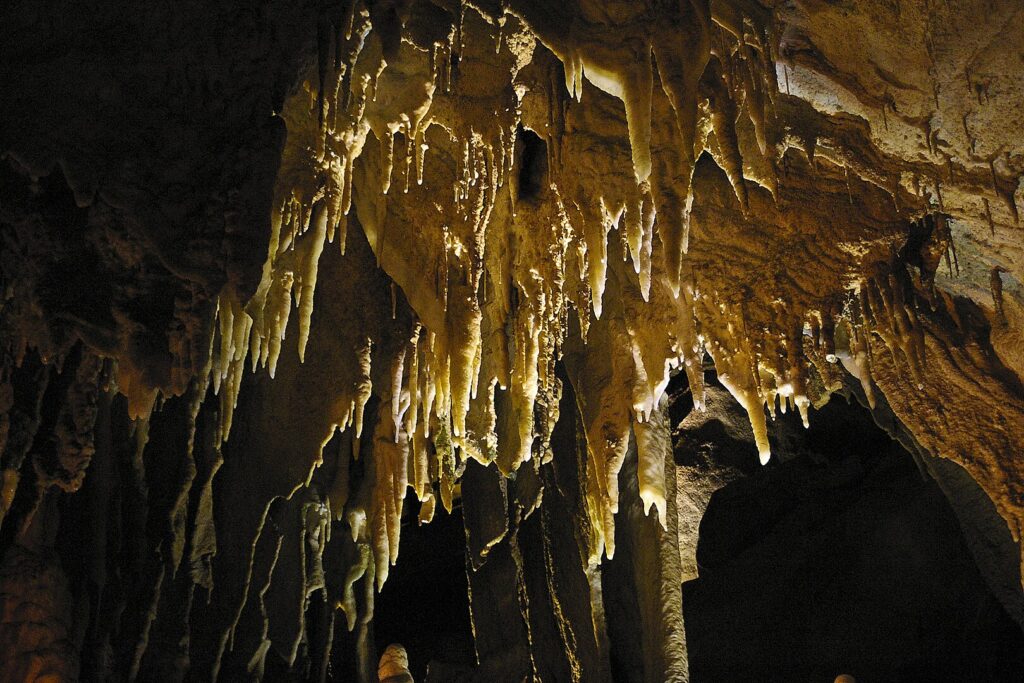

Beneath the scorching Chihuahuan Desert landscape of southern New Mexico lies the cool, otherworldly realm of Carlsbad Caverns National Park. The park’s main attraction, Carlsbad Cavern, features over 119 known caves formed when sulfuric acid dissolved the surrounding limestone, creating some of the most spectacular underground chambers in the world. The crown jewel is undoubtedly the Big Room, a massive underground chamber large enough to hold 14 football fields, adorned with countless stalactites, stalagmites, columns, and other decorative formations. Each evening from spring through fall, visitors gather at the cave’s natural entrance to witness one of nature’s most remarkable spectacles: the emergence of hundreds of thousands of Brazilian free-tailed bats spiraling out of the cave in search of night-flying insects.

Less visited but equally impressive is Lechuguilla Cave, discovered in 1986 and now known to extend for over 138 miles, containing some of the most pristine and scientifically valuable cave formations ever documented—including delicate crystal structures, massive gypsum chandeliers, and rare microbial communities that have led to medical research breakthroughs.

Wind Cave: Where Boxwork Creates a Geological Masterpiece

Wind Cave National Park in South Dakota protects one of the world’s most complex cave systems, characterized by an unusual formation called boxwork—an intricate honeycomb-like pattern of thin calcite fins that project from the walls and ceilings. While not the largest cave system, Wind Cave is remarkable for having the highest concentration of boxwork formations found anywhere on Earth, creating mesmerizing geometric patterns that appear almost artificial in their precision. The cave’s unusual name comes from the barometric winds at its natural entrance, where air either rushes in or out of the small opening depending on the relative atmospheric pressure between the cave and the surface.

Above ground, the park protects one of the few remaining mixed-grass prairie ecosystems in the United States, creating a dramatic contrast between the windswept surface landscape and the still, maze-like passages below. The cave also holds spiritual significance for several Native American tribes, including the Lakota who consider it the place from which their ancestors emerged into the world, adding cultural depth to this geological treasure.

Oregon Caves: The Marble Halls of Oregon

Nestled within the Siskiyou Mountains of southwestern Oregon, Oregon Caves National Monument and Preserve protects a rare marble cave system formed when acidic rainwater dissolved its way through solid marble rock over millions of years. Unlike many caves formed in limestone, these “Marble Halls” showcase distinctive bluish-white walls with swirling patterns created by mineral impurities in the metamorphic rock. The cave system maintains a constant cool temperature of around 44 degrees Fahrenheit, creating a stark contrast to the seasonal extremes experienced in the surrounding old-growth forest ecosystem.

Paleontologists have uncovered numerous significant fossils within the cave, including the nearly complete skeleton of a grizzly bear estimated to be 50,000 years old, providing insights into the prehistoric fauna of the region. The rustic, historic Oregon Caves Chateau, built in 1934 at the monument’s entrance, offers visitors a chance to experience the golden age of national park architecture while exploring this underground marble wilderness.

Jewel Cave: A Sparkling Underground Labyrinth

Jewel Cave National Monument in South Dakota protects the third-longest cave system in the world, with more than 208 miles of mapped passages—and new discoveries continue to expand its known dimensions. The cave earned its name from the walls of calcite crystals that sparkle like jewels when illuminated, creating a mesmerizing display unlike any other cave in the national park system. Beyond the namesake crystal formations, Jewel Cave features an astonishing variety of speleothems including delicate frostwork, dogtooth spar crystals, and cave popcorn formations that showcase the diversity of mineralization processes at work.

Exploration of Jewel Cave continues to this day, with survey teams regularly pushing deeper into the system through narrow crawlways that open into previously undiscovered chambers, suggesting that perhaps only a fraction of the cave’s true extent has been mapped. The ongoing discovery process makes Jewel Cave particularly exciting for speleologists, as each expedition holds the potential to uncover new wonders and expand our understanding of this vast underground wilderness.

Lava Tube Caves: Volcanic Underground Passages

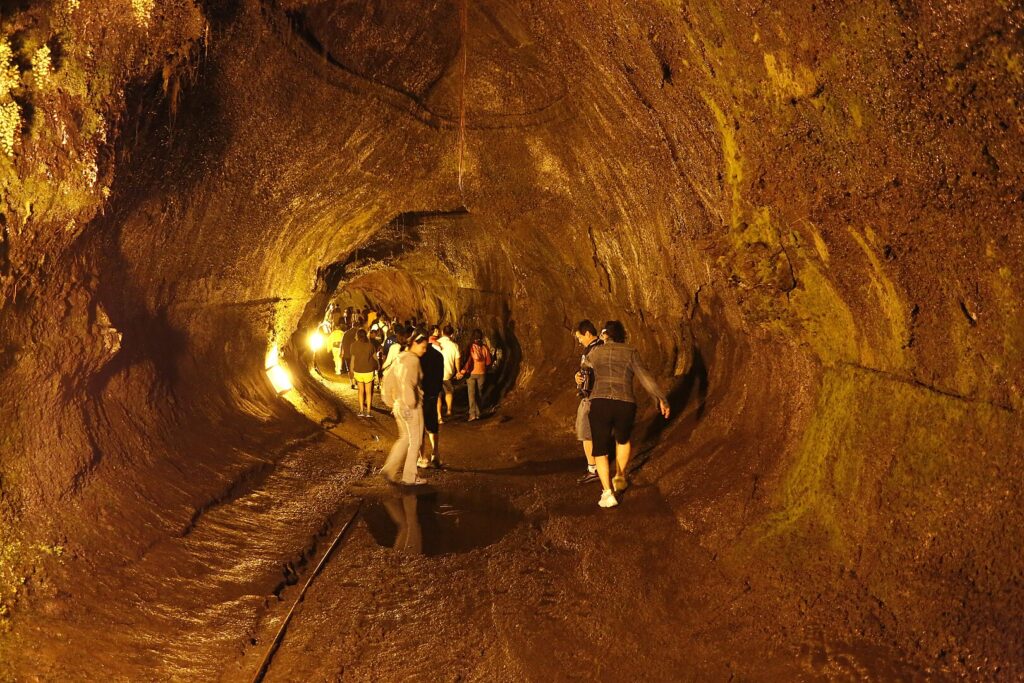

Entirely different from solution caves formed in limestone or marble, lava tube caves represent another fascinating category of underground features found in several national parks, particularly those with volcanic origins. These tubular passages form when the outer layer of flowing lava cools and hardens while the hotter inner channel continues to flow, eventually draining out and leaving behind a hollow conduit. Hawaii Volcanoes National Park contains numerous lava tubes, including the accessible Nahuku (Thurston Lava Tube), where visitors can walk through a 500-year-old volcanic tunnel once filled with rivers of molten rock.

Lava Beds National Monument in northern California protects one of the largest concentrations of lava tubes in the United States, with over 700 caves formed during eruptions of the Medicine Lake shield volcano over the past 500,000 years. Unlike solution caves with their decorative formations that build up over millennia, lava tubes feature smooth, rounded walls, “lavacicles” that hung from the ceiling while still molten, and occasionally vibrant colors from mineral deposits—providing a dramatic window into the power of volcanic processes that shaped the surrounding landscapes.

Russell Cave: A Window into Prehistoric Human Habitation

Russell Cave National Monument in northeastern Alabama preserves not only a geological wonder but also one of the most complete archaeological records of prehistoric human habitation in the eastern United States. The cave’s massive entrance chamber provided shelter for various indigenous groups for nearly 10,000 years, with archaeological excavations revealing layers of artifacts showing technological and cultural evolution from the Paleo-Indian period through Archaic, Woodland, and Mississippian cultural phases. The cave’s consistent internal temperature, natural water source, and protective overhang made it an ideal seasonal dwelling for early hunter-gatherers, who left behind stone tools, pottery fragments, weapons, and food remains that have helped archaeologists reconstruct daily life across dozens of generations.

The underground stream that flows through the lower levels of Russell Cave continues to carve new passages, demonstrating that even after millennia of human observation, the cave remains a dynamic, evolving system. Through careful preservation of this site, the National Park Service protects not only a geological formation but also an irreplaceable record of human adaptation and survival that spans most of post-Ice Age North American history.

Crystal Cave: Sequoia’s Underground Treasure

Hidden beneath the towering giant sequoias and rugged mountains of Sequoia National Park lies Crystal Cave, a marble karst system adorned with some of the most pristine formations in the Sierra Nevada range. The cave’s entrance, accessible only by guided tour during summer months, reveals itself as a spider web gate set in solid marble, behind which lies over three miles of surveyed passages decorated with curtains of flowstone, delicate soda straws, and massive ribbon draperies. Unlike many commercial caves that have suffered damage from unregulated visitation, Crystal Cave has been protected since its discovery in 1918, preserving delicate features including rare lillypad formations—thin calcite discs that form on the surface of cave pools.

The journey to Crystal Cave adds to its mystique, requiring visitors to descend a steep half-mile trail through a forest of oak, pine, and fir trees before arriving at the dramatically framed cave entrance. The underground stream flowing through the cave’s lower levels not only creates beautiful blue-green pools but continues the formation process, demonstrating that this underground environment remains a living, evolving system despite the apparent permanence of its stone surroundings.

Timpanogos Cave: Mountain Chambers with Vibrant Colors

Perched high in the steep limestone cliffs of American Fork Canyon in Utah’s Wasatch Range, Timpanogos Cave National Monument protects a system of three connected caves renowned for their unusually colorful formations. Visitors must climb a strenuous 1.5-mile trail that ascends over 1,000 feet in elevation to reach the cave entrance, making this one of the most physically demanding cave experiences in the national park system. The effort is rewarded with spectacular displays of helictites—twisted, gravity-defying formations that seem to grow in impossible directions—and the cave’s famous Great Heart of Timpanogos, a massive reddish-orange stalactite shaped remarkably like a human heart.

The vibrant colors throughout the cave system, ranging from deep reds and oranges to greens and browns, come from trace minerals in the limestone, creating a dramatic underground palette unlike the predominantly white formations found in many other cave systems. The caves’ elevation at over 6,700 feet above sea level contributes to their distinctive characteristics, as do the forces of plate tectonics that have tilted many of the formations at unusual angles, creating a uniquely dynamic appearance to these underground chambers.

Sea Caves: Where Underground Meets Underwater

Along the coastal boundaries of several national parks, a different type of subterranean wonder can be found where the relentless force of ocean waves has carved chambers and passageways into seaside cliffs. Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore along Michigan’s Lake Superior coast features colorful sandstone sea caves accessible primarily by kayak, where wave action has hollowed out chambers adorned with mineral-stained walls in vibrant reds, oranges, and browns. Channel Islands National Park off the coast of California protects remarkable sea caves including Painted Cave on Santa Cruz Island—one of the largest sea caves in the world at nearly a quarter-mile long with a dramatic 160-foot entrance.

At Apostle Islands National Lakeshore in Wisconsin, winter transforms the Lake Superior sea caves into ice caves when freezing temperatures create fantastic formations of ice stalactites, curtains, and crystal-clear frozen waterfalls that temporarily decorate the cave interiors. These dynamic environments, constantly shaped by water, represent the active interface between terrestrial and aquatic worlds, offering glimpses of geological processes still actively sculpting the landscape rather than the slower, more subtle changes occurring in dry caves.

The Fragile Ecology of Cave Environments

Cave ecosystems within national parks represent some of the most fragile and specialized environments on Earth, harboring unique species adapted to life in perpetual darkness, constant temperatures, and limited food resources. Troglobites—animals that live exclusively in caves—often display remarkable evolutionary adaptations including loss of pigmentation, reduced or absent eyes, enhanced sensory structures, and efficient metabolism for surviving in nutrient-poor environments. The delicate balance of these ecosystems can be disrupted by even minimal human interference, as oils from fingerprints can halt formation growth, introduced materials can alter the chemistry of cave pools, and artificial lighting can enable algae growth in environments that naturally lack photosynthetic organisms.

Caves also serve as important hibernation sites for several endangered bat species, making careful management of human visitation essential for protecting these mammals already threatened by white-nose syndrome—a fungal disease that has devastated bat populations across North America. The National Park Service employs specialized protocols for cave management, including decontamination procedures, limited visitor numbers, and seasonal closures to minimize human impact while still allowing appropriate public access to these extraordinary underground environments.

Scientific Discoveries and Ongoing Research in Park Caves

The caves within America’s national parks continue to serve as living laboratories where researchers make groundbreaking discoveries in fields ranging from geology and paleontology to microbiology and climate science. In Lechuguilla Cave at Carlsbad Caverns National Park, scientists have discovered microorganisms that exist by metabolizing sulfur and iron compounds, expanding our understanding of life in extreme environments and providing insights that may help in the search for extraterrestrial life. Researchers studying ancient calcite formations in caves throughout the park system are uncovering detailed records of past climate conditions, with each layer of deposit preserving information about temperature, precipitation, and atmospheric composition over thousands of years.

The discovery of previously unknown species continues at a remarkable pace, with biologists documenting new cave-adapted invertebrates, microbes with potential pharmaceutical applications, and complex food webs that function without sunlight as their primary energy source. These protected underground environments also serve as repositories of paleontological treasures, with recent discoveries including Ice Age mammal remains in caves throughout the Southwest and evidence of extinct species that help complete our understanding of North American ecological history.

Responsible Visitation: Experiencing Cave Wonders Sustainably

For visitors eager to experience the underground treasures of America’s national parks, responsible practices ensure these delicate environments remain protected for future generations. The National Park Service offers structured cave tours at many locations, with trained rangers providing both educational content and guidance on appropriate behavior that minimizes impact on the cave environment. The principle of “take nothing but pictures, leave nothing but footprints” takes on heightened importance in the cave environment, where even seemingly minor actions like touching formations can halt growth processes that have been ongoing for thousands of years.

Many parks have implemented specialized infrastructure to protect caves while allowing visitation, including airlock entrances that maintain natural air circulation patterns, carefully designed lighting systems that minimize heat and algae growth, and designated pathways that concentrate inevitable human impact to limited areas. Some particularly sensitive cave systems, including Lechuguilla Cave in New Mexico and significant portions of Jewel Cave in South Dakota, remain closed to general visitation, accessible only to researchers with specific scientific objectives—a necessary compromise that preserves these pristine environments while still advancing our knowledge of these remarkable underground worlds.

Conclusion

The underground landscapes protected within America’s national parks offer a profound counterpoint to the more familiar surface features that attract millions of visitors each year. These hidden realms—from the vast chambers of Mammoth Cave to the crystalline passages of Carlsbad Caverns—represent