Native plants form the backbone of thriving ecosystems, providing essential habitat and food sources for wildlife that have evolved alongside them for thousands of years. As habitat loss and environmental degradation threaten biodiversity worldwide, conservation efforts increasingly recognize the critical importance of restoring native plant communities. This article explores how indigenous flora serves as a catalyst for wildlife recovery, examining successful restoration projects, ecological relationships, and how everyday citizens can contribute to this vital conservation strategy.

The Ecological Foundation: Why Native Plants Matter

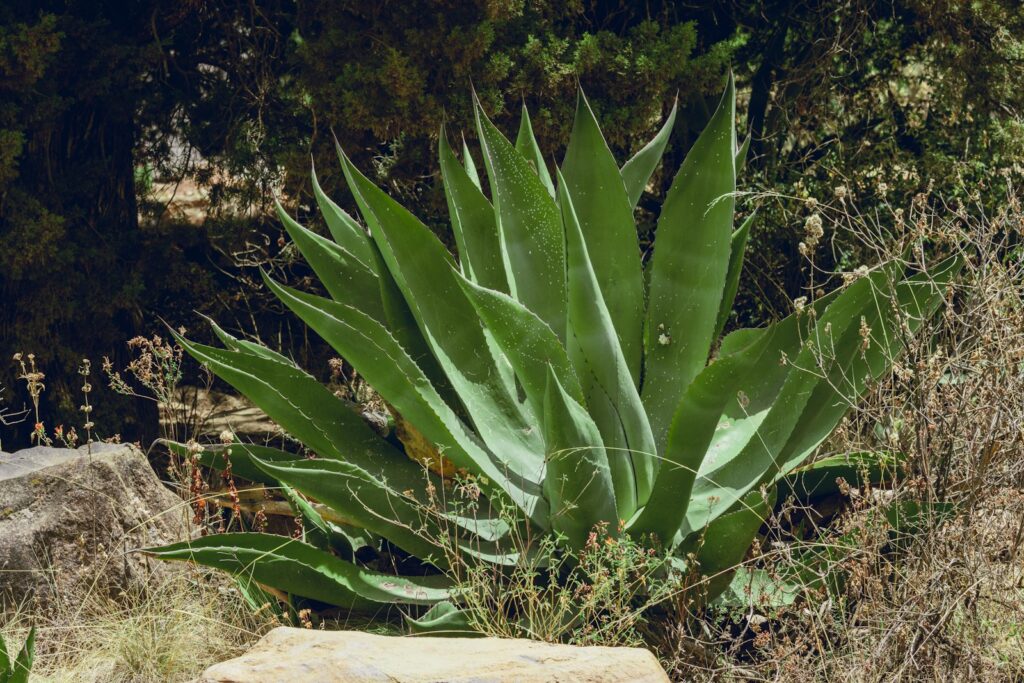

Native plants are species that have evolved within specific geographic regions over thousands of years, developing complex relationships with the local wildlife, soil microorganisms, and climate conditions. These indigenous plant species form the foundation of food webs, providing nutrients that flow through entire ecosystems, from insects to apex predators. Unlike non-native ornamentals, native plants require less maintenance, fewer resources, and no chemical fertilizers or pesticides to thrive, making them environmentally sustainable choices for habitat restoration. The deep root systems of many native plants also help prevent erosion, filter water pollutants, and sequester carbon, providing ecosystem services that extend far beyond wildlife habitat.

Coevolution: The Dance Between Plants and Wildlife

The relationship between native plants and wildlife represents one of nature’s most remarkable examples of coevolution, where species develop in tandem over millennia. Many native pollinators, for instance, have mouthparts precisely adapted to extract nectar from specific flower shapes, while those plants depend on those same insects for reproduction. Monarch butterflies offer a classic example, as their caterpillars can only survive on milkweed plants, which produce toxins that most insects cannot tolerate but monarchs have adapted to incorporate into their own defense mechanisms. These specialized relationships explain why non-native plants, despite sometimes providing general resources like nectar, cannot fully replace the ecological functions of native species. When we remove native plants from an ecosystem, we don’t just lose the plants themselves but potentially disrupt dozens of wildlife species that depend on them.

The Pollinator Crisis and Native Plant Solutions

Pollinator populations worldwide face unprecedented declines, with severe implications for both natural ecosystems and human food security. Native plant restoration has emerged as a powerful strategy to address this crisis, providing essential habitat for bees, butterflies, moths, and other pollinating species. Research consistently demonstrates that native plant gardens support significantly higher pollinator diversity and abundance compared to conventional landscapes dominated by non-native ornamentals. Even small native plant patches can serve as “stepping stones” that help pollinators navigate through otherwise inhospitable urban and suburban environments. The timing of native plant flowering is also precisely aligned with the life cycles of local pollinators, ensuring resources are available throughout the growing season when wildlife needs them most.

Bird Recovery Through Native Plant Restoration

Birds represent one of the most visible wildlife groups to benefit from native plant restoration efforts. Native trees, shrubs, and grasses provide crucial nesting sites, protective cover, and food sources that exotic plants simply cannot match. A landmark study by the University of Delaware found that native oak trees support over 550 species of caterpillars—a primary food source for nestling birds—while non-native ginkgo trees host just five species. This dramatic difference explains why areas with native vegetation typically support significantly more bird species and individuals than similar habitats dominated by non-native plants. Conservation organizations like the National Audubon Society have developed successful programs connecting bird recovery directly to native plant restoration, demonstrating measurable increases in both common and threatened bird populations where native habitats have been restored.

Mammals and Native Plant Communities

From tiny shrews to imposing bears, mammals of all sizes depend on native plant communities for their survival and recovery. Native plants provide the appropriate nutritional profiles that local mammals have evolved to digest, offering essential calories, proteins, and micronutrients at the right times of year. For herbivorous mammals like deer and rabbits, native plants offer browse material that aligns with their digestive systems and nutritional needs, while carnivores benefit indirectly as healthy plant communities support robust prey populations. In fragmented landscapes, corridors of native vegetation allow mammals to move safely between habitat patches, supporting genetic diversity and helping populations remain resilient. The timing of native plant fruiting and seeding also synchronizes perfectly with the seasonal needs of local mammals, particularly those preparing for migration or hibernation.

Reptiles and Amphibians: Overlooked Beneficiaries

Reptiles and amphibians—collectively known as herpetofauna—often receive less attention in conservation discussions but benefit tremendously from native plant restoration. The structural diversity provided by native vegetation creates essential microhabitats that help these animals regulate their body temperature, a critical requirement for ectothermic species. Native plant communities adjacent to aquatic habitats are particularly important for amphibians, which typically require both aquatic environments for breeding and terrestrial habitats for foraging and overwintering. Many reptiles, including threatened turtle and snake species, depend on specific native plant communities to support their prey base and provide secure nesting sites. The complex root systems of native plants also create underground passageways and hibernation sites that help herpetofauna survive extreme weather and predation pressure.

Insect Biodiversity and Ecological Resilience

Insects form the foundation of terrestrial food webs, and their diversity and abundance are inextricably linked to native plant communities. Research consistently shows that native plants support exponentially more insect species than non-natives, with specialist relationships that have developed over evolutionary time. Beyond the well-known pollinator connections, native plants support countless herbivorous insects that have adapted to overcome the specific chemical defenses of local plant species. These plant-eating insects then become food for predatory insects, creating complex food webs that support overall ecosystem health and resilience. The relationship is so specific that entomologist Doug Tallamy found that non-native plants support 29 times fewer insects than natives, creating ecological “dead zones” where introduced ornamentals dominate the landscape.

Prairie Restoration Success Stories

North American prairies once covered nearly a billion acres, supporting some of the continent’s richest wildlife assemblages before being reduced to less than 1% of their original extent. Modern prairie restoration efforts showcase the remarkable wildlife recovery potential of native plant communities. The Neal Smith National Wildlife Refuge in Iowa transformed 8,000 acres of farmland back to tallgrass prairie, documenting the return of over 200 bird species and dozens of mammals, including the reintroduction of bison. The Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie in Illinois converted a former ammunition plant into thriving grassland habitat, now supporting rare grassland birds like Henslow’s sparrows and bobolinks that had disappeared from the region. These restoration projects demonstrate that even severely degraded landscapes can recover substantial wildlife diversity when the appropriate native plant communities are reestablished, though the process may take decades to fully develop.

Wetland Restoration Through Native Aquatic Plants

Wetlands rank among Earth’s most productive ecosystems, and native aquatic and riparian plants play central roles in their ecological function and wildlife support. Restoration projects incorporating native wetland plants have demonstrated remarkable wildlife comebacks, often within just a few years of implementation. Native emergent plants like cattails, bulrushes, and sedges provide essential nesting habitat for waterfowl and shelter for juvenile fish, while submerged aquatics create oxygen-rich environments for aquatic invertebrates that form the base of wetland food webs. Along wetland margins, native trees and shrubs like willows and buttonbush offer perching sites for fishing birds and shade that helps maintain appropriate water temperatures for sensitive amphibians. These comprehensive wetland restoration approaches have contributed to the recovery of numerous threatened species, from wood ducks to western pond turtles.

Urban Wildlife Corridors and Native Plants

Urban and suburban landscapes represent some of the fastest-growing habitat types worldwide, making native plant integration in developed areas increasingly crucial for wildlife conservation. Cities that have incorporated native plant corridors along greenways, stream buffers, and transportation rights-of-way have documented significant increases in urban wildlife diversity and abundance. Chicago’s award-winning urban wildlife corridor system connects fragmented habitat patches with native plantings, helping species move safely through the urban matrix while providing essential breeding and foraging habitat. Even small-scale urban native plant installations, such as curbside rain gardens and green roofs, contribute meaningfully to urban biodiversity when designed with appropriate local species. Research consistently shows that urban areas with higher native plant diversity support correspondingly higher wildlife diversity, creating healthier ecosystems that benefit both wildlife and human residents.

Challenges in Native Plant Restoration

Despite its proven benefits, native plant restoration faces significant challenges that can complicate wildlife recovery efforts. Invasive species often outcompete newly established natives, requiring ongoing management to ensure restoration success, particularly in the critical early establishment phase. Climate change further complicates restoration work as traditional native plant ranges shift, raising difficult questions about what constitutes “native” in rapidly changing ecosystems. The limited commercial availability of locally adapted native plant materials presents another obstacle, as many restoration projects must rely on seed sources from distant populations that may be less well-adapted to local conditions. Social challenges also exist, including aesthetic preferences for traditional horticultural landscapes and misconceptions about native plants being “messy” or requiring less maintenance, when in reality, they simply require different management approaches tailored to their natural growth habits.

Native Plants in Your Backyard: Individual Conservation Impact

Individual property owners collectively manage millions of acres of potential wildlife habitat, making personal native plant gardens crucial components of broader conservation efforts. Even small residential native plant installations can support remarkable wildlife diversity, with studies documenting hundreds of insect species and dozens of bird species utilizing well-designed home gardens. Native plant gardens provide essential “stepping stones” that help wildlife navigate through otherwise inhospitable developed landscapes, supporting species movement and gene flow. Homeowners can maximize their conservation impact by focusing on keystone native plant species that support particularly high numbers of wildlife species, such as native oaks, cherries, willows, and goldenrods. By gradually replacing non-native ornamentals with region-appropriate natives, individual property owners become important participants in landscape-scale conservation networks that support wildlife recovery across property boundaries.

The Future of Conservation: Integrated Native Plant Approaches

The future of effective wildlife conservation increasingly centers on integrated approaches that recognize native plants as fundamental building blocks of functioning ecosystems. Rather than focusing solely on charismatic animal species, modern conservation emphasizes restoring the plant communities that support entire ecological communities. This paradigm shift acknowledges that successful wildlife recovery requires attention to all trophic levels, from soil microorganisms to apex predators, with native plants forming the critical foundation. Emerging conservation models also emphasize connectivity between habitat patches, recognizing that isolated reserves are insufficient for long-term species survival in rapidly changing environments. As climate change accelerates, the genetic diversity contained within native plant populations represents a crucial resource for adaptation, making the preservation of diverse native plant communities an essential climate resilience strategy that benefits wildlife across taxonomic groups.

Conclusion

The intrinsic connection between native plants and wildlife health has become increasingly evident as restoration projects demonstrate remarkable species recoveries when indigenous plant communities are reestablished. From urban backyards to landscape-scale prairie reconstructions, native plants provide the ecological foundation that makes wildlife comebacks possible. As we face unprecedented biodiversity challenges, this understanding offers a hopeful path forward: by restoring the plant communities that have supported local wildlife for millennia, we can help reverse declines and create more resilient ecosystems. Whether through large conservation initiatives or individual garden transformations, native plant restoration represents one of our most powerful tools for ensuring that future generations inherit a world rich in wildlife diversity.