The silent depths of our oceans host some of Earth’s most diverse and vibrant ecosystems, from kaleidoscopic coral reefs to mysterious deep-sea habitats. Yet these underwater wonderlands face unprecedented threats from human activities, climate change, and resource exploitation. Marine national parks represent one of humanity’s most effective responses to these challenges, establishing protected areas where marine life can thrive under reduced pressure from destructive activities. These sanctuaries serve as underwater havens where biodiversity is prioritized, scientific research flourishes, and sustainable practices are developed. As our understanding of marine conservation evolves, these parks increasingly demonstrate their vital role in preserving ocean health for future generations, balancing environmental protection with human needs in a delicate but essential equilibrium.

The Fundamental Purpose of Marine National Parks

Marine national parks serve as designated areas in ocean and coastal environments where marine ecosystems receive legal protection from harmful human activities. Unlike terrestrial parks, these protected areas safeguard underwater habitats that would otherwise remain vulnerable to fishing pressure, resource extraction, and pollution. Their primary mission combines conservation, education, research, and sustainable recreation to ensure marine biodiversity preservation. These parks establish boundaries within which human impacts are carefully managed, regulated, or prohibited entirely, creating refuges where marine life can recover and flourish with minimal disturbance. By balancing protection with appropriate human access, marine parks represent a pragmatic approach to ocean conservation that recognizes both ecological needs and human interests.

Creating Biodiversity Hotspots Through Protection

Within well-managed marine protected areas, studies consistently demonstrate significant increases in species abundance, diversity, and biomass compared to adjacent unprotected waters. When fishing pressure decreases or ceases entirely within park boundaries, fish populations naturally recover, often growing larger and more numerous within just a few years of protection. These recovering populations create cascading benefits throughout the ecosystem, as larger predatory fish help maintain balance among species at lower trophic levels. Research in places like Australia’s Great Barrier Reef Marine Park shows that protected zones contain up to twice the large fish biomass compared to areas where fishing is permitted. This biodiversity enhancement extends beyond fish to affect invertebrates, marine mammals, reptiles, and even microscopic organisms that form the foundation of marine food webs, creating resilient underwater communities.

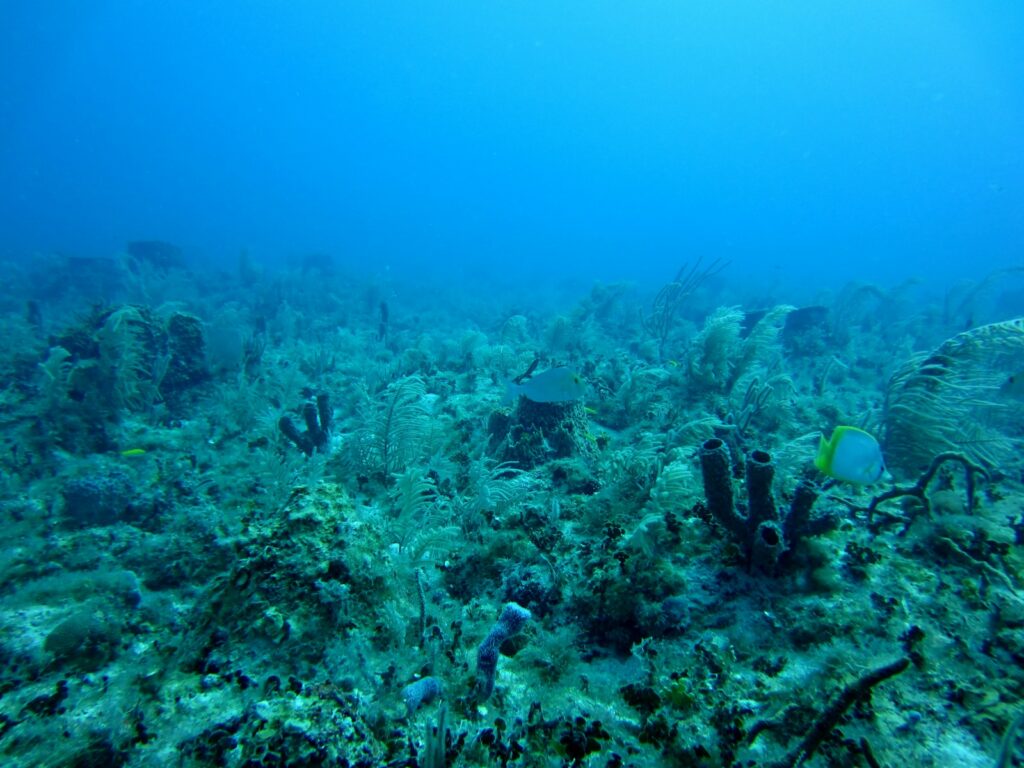

Safeguarding Critical Habitats from Destruction

Marine parks provide essential protection for vulnerable habitats that serve as the foundation for ocean ecosystems. Coral reefs, which support approximately 25% of all marine species despite covering less than 1% of the ocean floor, receive vital protection from destructive fishing practices, anchor damage, and pollution within park boundaries. Seagrass meadows, which sequester carbon at rates exceeding terrestrial forests while providing nursery grounds for countless species, benefit from reduced physical disturbance and improved water quality in protected areas. Mangrove forests, which protect coastlines from erosion while filtering pollutants and nurturing juvenile marine life, face fewer threats from development and exploitation when included in marine parks. Deep-sea habitats like hydrothermal vents and seamounts, which host unique life forms adapted to extreme conditions, increasingly receive protection from bottom trawling and resource extraction through marine park designations that recognize their irreplaceable ecological value.

Establishing Reproductive Sanctuaries

One of the most valuable functions of marine protected areas is their role as reproductive havens where marine species can complete their life cycles with minimal human interference. Many commercially valuable fish species gather in specific locations to spawn, making them particularly vulnerable to fishing during these critical reproductive periods. Marine parks that encompass spawning aggregation sites ensure that fish can reproduce successfully, producing billions of eggs and larvae that support population renewal. Protected areas also safeguard the habitats necessary for juvenile development, such as mangroves and seagrass beds that serve as nurseries for young fish before they migrate to adult habitats. Research demonstrates that marine reserves containing intact reproductive populations produce larval exports that can travel significant distances on ocean currents, replenishing fish stocks in surrounding waters through a “spillover effect.” This biological connectivity between protected and unprotected areas highlights how marine parks benefit ecosystems and fisheries well beyond their boundaries.

Fostering Ecosystem Resilience Against Climate Change

As climate change intensifies, marine protected areas serve as crucial buffers against its devastating effects on ocean ecosystems. By reducing or eliminating local stressors like overfishing and pollution, marine parks help ecosystems maintain resilience when facing climate-related challenges such as rising temperatures and ocean acidification. Research indicates that protected coral reefs recover from bleaching events up to four times faster than unprotected reefs, as reduced fishing pressure allows herbivorous fish populations to thrive and control algae that would otherwise smother recovering corals. Marine parks also protect carbon-sequestering habitats like seagrass meadows, mangroves, and salt marshes, which collectively store “blue carbon” at rates exceeding terrestrial forests. By designing networks of marine protected areas that account for predicted climate shifts, conservationists create potential climate refugia where vulnerable species might persist as conditions change elsewhere. This forward-thinking approach to marine protection acknowledges that static boundaries may become less effective as species ranges shift in response to changing ocean conditions.

Advancing Scientific Knowledge Through Research Opportunities

Marine national parks serve as living laboratories where scientists can study relatively intact marine ecosystems, establishing baseline conditions against which to measure environmental changes elsewhere. These protected areas provide invaluable opportunities for long-term monitoring programs that track ecosystem health, species populations, and environmental conditions over decades, generating data sets that would be impossible to collect in heavily exploited regions. Researchers within marine parks can observe natural ecological processes with minimal human interference, gaining insights into predator-prey relationships, competition between species, and recovery patterns following disturbances. The knowledge gained from marine park research directly informs conservation efforts worldwide, helping managers design more effective protection measures based on empirical evidence rather than theoretical models. Additionally, many marine parks maintain research facilities and partner with academic institutions, creating collaborative opportunities for scientists while building capacity for marine conservation in local communities.

Supporting Sustainable Fisheries Through Spillover Effects

Despite initial resistance from some fishing communities, evidence increasingly demonstrates that marine protected areas ultimately benefit fisheries through biological spillover effects. As fish populations rebuild within no-take zones, adult fish naturally migrate into surrounding waters where they become available to fishers, a process documented in numerous studies worldwide. The protected breeding populations within marine parks produce larvae that disperse on ocean currents, eventually replenishing fish stocks in fishing grounds outside park boundaries. Fishers in communities adjacent to well-enforced marine reserves often report increases in catch per unit effort over time, as they target the “edge effect” where fish abundance is enhanced near reserve boundaries. The economic benefits extend beyond just increased catch, as fish from protected areas tend to be larger, commanding higher market prices and providing better reproductive potential for future generations. This fisheries enhancement represents one of the most compelling arguments for marine protection, demonstrating how conservation and sustainable resource use can work in harmony.

Protecting Cultural and Historical Maritime Heritage

Beyond their ecological value, many marine national parks preserve underwater cultural resources that connect humanity with its maritime history. Shipwrecks protected within marine parks provide windows into past eras, from ancient trading vessels to World War II battleships, preserved in underwater environments where they remain protected from salvage operations and treasure hunting. These submerged archaeological sites offer unique opportunities for historical research and education while serving as artificial reefs that support diverse marine life. Indigenous communities’ traditional connections to marine environments receive recognition and protection in many marine parks, acknowledging cultural fishing practices and sacred sites that have sustained coastal peoples for thousands of years. Marine parks often collaborate with indigenous groups to incorporate traditional ecological knowledge into management practices, recognizing that cultural and natural heritage are deeply intertwined in many coastal regions. This cultural dimension of marine protection enriches our understanding of human-ocean relationships while ensuring that maritime heritage remains accessible for future generations.

Developing Models for Sustainable Ocean Tourism

Well-managed marine national parks demonstrate how tourism and conservation can coexist, providing economic alternatives to extractive industries while fostering appreciation for marine ecosystems. Visitor facilities within marine parks introduce millions of people to underwater wonders through snorkeling, diving, glass-bottom boat tours, and interactive displays, creating emotional connections that inspire conservation support. Tour operators within park boundaries typically follow strict guidelines designed to minimize environmental impacts, establishing best practices that often influence the broader tourism industry. The economic value generated through sustainable marine tourism frequently exceeds what could be gained from extractive uses of the same areas, providing compelling economic justification for protection. Local communities adjacent to successful marine parks often experience economic revitalization through tourism-related businesses, creating stakeholders who actively support and defend marine conservation measures. This transformation from extraction-based economies to service-oriented ones represents a sustainable development pathway for coastal communities worldwide.

Challenges in Effective Marine Park Management

Despite their proven benefits, marine national parks face significant challenges that can undermine their effectiveness if not properly addressed. Enforcement difficulties present perhaps the greatest challenge, as patrolling vast marine areas requires substantial resources that many park authorities lack, especially in developing nations where “paper parks” exist on maps but receive little practical protection. Climate change impacts increasingly threaten protected ecosystems through coral bleaching, storm intensity, and changing species distributions that may render static boundaries less effective over time. Balancing stakeholder interests remains perpetually challenging, as different user groups—from commercial fishers to recreational divers to indigenous communities—may have competing visions for how marine areas should be managed. Sustainable financing mechanisms represent another critical challenge, as many marine parks struggle to secure consistent funding for patrol vessels, monitoring programs, staff salaries, and community engagement initiatives. Addressing these challenges requires innovative approaches, international cooperation, and recognition that effective marine protection demands long-term commitment beyond simply drawing boundaries on maps.

International Cooperation in Marine Conservation

The interconnected nature of ocean ecosystems necessitates international cooperation in marine protection, as currents, migratory species, and pollution cross political boundaries without regard for national jurisdiction. Transboundary marine protected areas demonstrate how neighboring countries can coordinate conservation efforts, with examples like the Red Sea Marine Peace Park (established by Israel and Jordan) showing how marine protection can even foster cooperation between nations with otherwise tense relations. Regional networks of marine protected areas, such as the Coral Triangle Initiative involving six Southeast Asian nations, create ecological corridors that maintain connectivity for migratory species while building cooperative management capacity. International agreements like the Convention on Biological Diversity’s target to protect 30% of ocean areas by 2030 establish shared goals that drive national marine protection efforts. The recent High Seas Treaty negotiations represent a landmark effort to establish protected areas in international waters beyond national jurisdictions, addressing a significant gap in ocean governance. These cooperative efforts acknowledge that effective marine conservation demands thinking beyond traditional boundaries toward shared stewardship of our global ocean commons.

Community Involvement and Indigenous Stewardship

Successful marine protected areas increasingly recognize that local community involvement in management decisions leads to more effective outcomes than top-down approaches imposed without consultation. Co-management arrangements between government authorities and local communities create shared responsibility for marine park governance, incorporating traditional knowledge alongside scientific research in decision-making processes. Locally managed marine areas (LMMAs) in the Pacific Islands demonstrate how communities can take primary responsibility for protecting nearby waters, using traditional conservation practices reinforced by modern legal recognition. Indigenous-led marine protection initiatives, such as those established by First Nations in British Columbia and Aboriginal communities in Australia, reconnect traditional custodians with their ancestral waters while providing effective protection based on millennia of ecological knowledge. Economic benefit-sharing mechanisms, from tourism revenue to sustainable fishing privileges, ensure that conservation creates tangible advantages for those most affected by protection measures. This evolution toward inclusive marine park governance recognizes that sustainable protection ultimately depends on the support and involvement of those who live closest to these precious marine resources.

The Future of Marine National Parks in Ocean Conservation

As marine protection evolves, several emerging trends suggest promising directions for the future of ocean conservation through protected areas. Dynamic management approaches using real-time data from satellites and ocean sensors allow marine park boundaries to shift in response to animal migrations or changing ocean conditions, creating more adaptive protection than static boundaries permit. Vertical zoning recognizes that different depths may require different management approaches, with surface waters potentially allowing activities prohibited in sensitive benthic habitats or vice versa. Marine protected area networks designed with climate resilience in mind increasingly incorporate projected climate refugia where conditions may remain suitable for vulnerable species as surrounding areas change. Technological innovations in enforcement, from drone surveillance to satellite monitoring, promise to address one of the greatest challenges facing marine parks by making illicit activities more detectable even in remote locations. As international momentum builds toward the target of protecting 30% of ocean areas by 2030, marine national parks will undoubtedly play a central role in this ambitious vision for ocean conservation at a truly meaningful scale.

Conclusion

Marine national parks stand as beacons of hope in our efforts to preserve the ocean’s remarkable biodiversity and ecological functions. These protected areas demonstrate that with proper management, enforcement, and community engagement, marine ecosystems can recover from degradation and thrive even as pressures mount elsewhere. From local fisheries benefits to global climate resilience, marine parks deliver multiple services that support both environmental and human wellbeing. As we face unprecedented challenges from climate change, pollution, and resource exploitation, expanding and strengthening these underwater sanctuaries represents one of our most powerful tools for ensuring healthy oceans for future generations. By combining scientific knowledge with traditional wisdom, technological innovation with community stewardship, marine national parks point the way toward a sustainable relationship with our blue planet—one where protection and prosperity go hand in hand.