America’s national parks aren’t just geological wonders—they are living monuments to the deep spiritual and cultural connections that Native American tribes have maintained with these landscapes for thousands of years. Long before these areas were designated as protected parks, they were sacred spaces, hunting grounds, and homes to Indigenous peoples who wove rich tapestries of legends and myths around these natural features. These stories not only explained the creation of stunning landscapes but also encoded moral teachings and cultural values that guided generations. Today, as millions of visitors marvel at these natural wonders, few realize they’re walking through living storybooks of Native American heritage.

Yosemite Valley: The Legend of Tis-sa-ack

Before Yosemite became one of America’s most celebrated national parks, it was home to the Ahwahnechee people who knew it as “Ahwahnee,” meaning “big mouth.” The iconic Half Dome, rising nearly 5,000 feet from the valley floor, features prominently in the legend of Tis-sa-ack and her husband. According to Miwok and Paiute tradition, Tis-sa-ack was a young woman who traveled to the valley during a drought, carrying a heavy basket of acorns. Exhausted and thirsty, she drank all the water from a lake without offering any to her husband, who grew angry and struck her in retaliation. The Creator punished their quarrel by transforming them into stone—Tis-sa-ack became Half Dome, her tear-streaked face visible in the dark streaks that run down its granite surface, while her husband was transformed into Washington Column, another prominent Yosemite formation.

Grand Canyon: Home of the Havasupai Creation Story

The Havasupai people, whose name means “people of the blue-green waters,” have lived in the Grand Canyon for at least 800 years and consider it their sacred ancestral homeland. Their creation story tells of the god Tochopa, who created the Havasupai and directed them to be guardians of the Grand Canyon. According to their tradition, a great flood once covered the world, from which Tochopa saved his daughter Pukeheh by sealing her in a hollow log. When the waters receded, she emerged, and the wind impregnated her, giving birth to the Havasupai people. The striking red color of the canyon walls is said to represent the blood of their ancestors, while the blue-green waters of Havasu Creek symbolize life and renewal in this harsh desert environment. The Havasupai continue to live within the Grand Canyon today, maintaining their status as the only tribe to reside entirely within Grand Canyon National Park boundaries.

Yellowstone: The Sacred Thermal Features of Many Tribes

Yellowstone, America’s first national park, was never permanently inhabited but served as hunting grounds and a spiritual crossroads for multiple tribes, including the Blackfeet, Shoshone, Bannock, and Crow. The park’s spectacular thermal features, especially the geysers and hot springs, were viewed as manifestations of powerful spirits and often featured in origin stories. The Kiowa people tell of a warrior who transformed into a bear and scratched the earth with massive claws, creating the park’s geothermal features. The Shoshone and Bannock believed the geysers’ steam and bubbling mud were communications from the spirit world, and they often left offerings near thermal features before hunts. Many tribes considered bathing in or near certain hot springs a sacred purification ritual that could heal both physical and spiritual ailments. These thermal features were so revered that they were considered neutral territory, where even rival tribes would temporarily set aside conflicts.

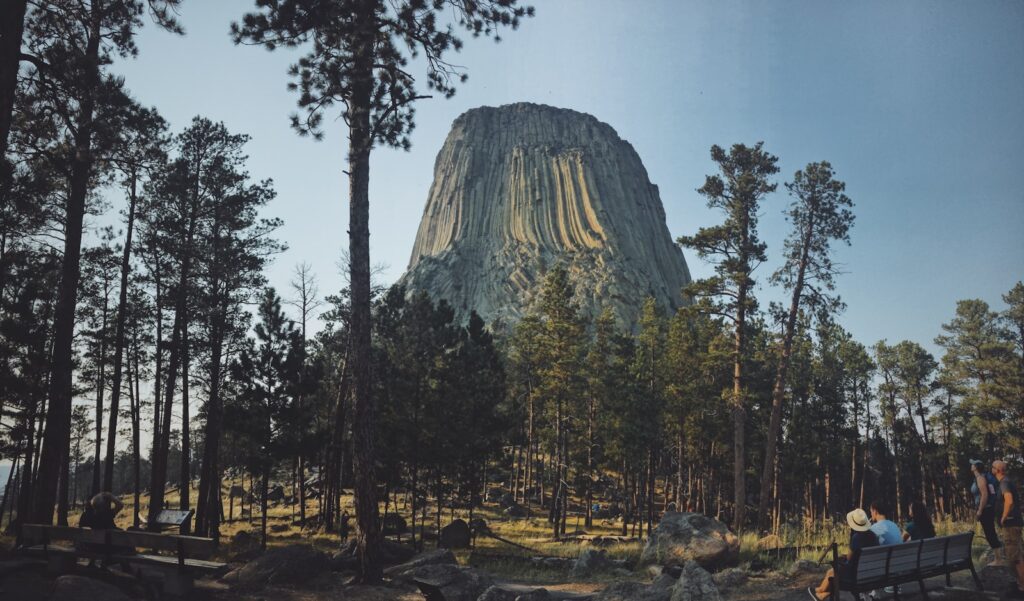

Devil’s Tower: The Sacred Bear Lodge

Rising dramatically from the Wyoming plains, Devil’s Tower (or Bear Lodge) holds profound significance for numerous Plains tribes, including the Lakota, Cheyenne, Kiowa, and Crow. While European settlers named it Devil’s Tower, many Native tribes knew it as Bear Lodge or Bear’s Tipi. The Kiowa tell of seven sisters who were pursued by a giant bear; as the bear clawed at the rock where they sought refuge, it created the tower’s distinctive vertical striations, while the sisters became the constellation known today as the Pleiades. The Lakota version describes children being chased by a giant bear, with the Great Spirit raising the ground beneath them to safety; as the bear clawed the sides, it created the fluted columns visible today. These legends explain not only the tower’s unique geological characteristics but also emphasize courage, divine protection, and the sacred relationship between humans, animals, and cosmic forces. Even today, numerous prayer bundles and cloth offerings can be found tied to trees around the tower’s base, evidence of continued spiritual practices.

Mesa Verde: The Ancestral Pueblo Mystery

The remarkable cliff dwellings of Mesa Verde National Park represent one of the most significant archaeological preserves of ancestral Puebloan culture in the United States. According to Hopi traditions, who consider themselves descendants of the cliff dwelling builders, these structures weren’t abandoned due to drought or conflict as archaeologists once theorized, but were part of a divinely guided migration. Hopi oral traditions speak of several worlds or eras of existence, with migrations marking transitions between these periods. These elaborate dwellings, tucked within protective cliff alcoves, were created as the Ancestral Puebloans fulfilled their covenant to leave their mark across the land before moving onward. The spiral petroglyphs found throughout the park represent this journey through different worlds, while hand prints pressed into mortar symbolize the enduring presence of ancestors. The Hopi consider these sites not abandoned ruins but living shrines where the spirits of their ancestors still dwell, serving as reminders of their historical journey and cultural covenant.

Glacier National Park: The Sacred Peaks of the Blackfeet

To the Blackfeet Nation, the mountains of what is now Glacier National Park are known as the “Backbone of the World,” a sacred landscape where vision quests and spiritual ceremonies have been conducted for countless generations. Chief Mountain, a distinctive standalone peak visible from great distances, was particularly venerated as a place where the physical and spiritual worlds intersect. Blackfeet legend tells of Star Boy, who fell from the sky and later became Scarface, a hero who journeyed to the Sun’s lodge via Chief Mountain to have a facial scar removed, establishing key Blackfeet rituals and societal structures upon his return. The park’s pristine waters were also sacred, particularly St. Mary Lake, where the Blackfeet conducted medicine lodge ceremonies. The mountains themselves were considered the dwelling places of powerful spirits, including wind-makers, thunder beings, and the legendary trickster figure Napi (Old Man), who was said to have formed the landscape during the world’s creation and taught the Blackfeet how to live and conduct ceremonies.

Great Smoky Mountains: Cherokee Land of Blue Smoke

The misty peaks of the Great Smoky Mountains have been home to the Cherokee people for thousands of years, who called them “Shaconage,” meaning “place of blue smoke”—a reference to the natural haze that gives the range its name. Cherokee creation stories tell of a time when the earth was covered with water, and animals lived above in Galunlati, the sky world. When the earth began to dry, they sent a water beetle to bring up mud, which expanded to form the mountains where the animals came to live. Later, the Creator placed the first Cherokee in these mountains, teaching them to live in harmony with the land and animals. One of the most sacred sites was Clingmans Dome, known to the Cherokee as Kuwahi or “mulberry place,” believed to be the home of the thunderbirds who brought storms and the highest council grounds where wise medicine men would gather. Today, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians still resides adjacent to the park, maintaining cultural connections to this landscape through traditional crafts, language preservation, and ceremonial practices that honor their ancestral homeland.

Arches National Park: Ute Territory of Standing People

The otherworldly landscape of Arches National Park, with its more than 2,000 natural stone arches, was historically the territory of the Ute people, who viewed these formations not as geological curiosities but as manifestations of spiritual power. The Ute referred to the remarkable balanced rocks and arches as “untu-weap” or “standing people,” believing them to be transformed ancestors watching over the land. Delicate Arch, the park’s most famous formation, was particularly significant in Ute cosmology, considered a gateway between the physical and spiritual worlds where medicine people could communicate with spirit helpers. Rock art panels throughout the area, some dating back thousands of years, depict supernatural beings, hunting scenes, and celestial observations that mapped both physical and spiritual relationships with this challenging landscape. The Ute considered passage through certain arches a form of spiritual rebirth and renewal, with seasonal ceremonies timed to celestial alignments visible through specific arch formations.

Mount Rainier: The Mother of Waters in Coast Salish Tradition

Towering over the Pacific Northwest landscape, Mount Rainier has been known by many Indigenous names, including “Tahoma” and “Tacoma,” meaning “the mother of waters” in several Coast Salish languages. The Puyallup people tell of a time when the mountain was a beautiful woman who gave birth to waters that nourished all living things; when a jealous neighboring mountain tried to steal her, a great battle erupted, damaging her face (the current crater) but establishing her permanent place in the landscape. The Nisqually people considered the mountain a sacred place where their ancestors retreated during a great flood, with specific locations on the mountain marking places where tribal elders received spiritual guidance. Many Coast Salish peoples gathered specific medicinal plants that grew only on the mountain’s slopes, believing they possessed enhanced healing properties due to the mountain’s spiritual nature. The predictable pattern of snow melt and river flows from the mountain also informed seasonal subsistence patterns, with tribes moving between elevation zones to harvest resources as they became available, creating a cycle that was both practical and deeply spiritual.

Everglades: The Seminole’s River of Grass

What many see as an inhospitable swamp, the Seminole and Miccosukee people recognize as a life-giving landscape that sheltered them during their darkest hours. When these tribes faced relentless persecution during the Seminole Wars of the 19th century, they retreated deep into the Everglades, where their intimate knowledge of this complex ecosystem allowed them to evade capture while maintaining their traditional lifeways. Seminole creation stories speak of the Breathmaker who created the Everglades as a special gift to the tribe, with the sawgrass, cypress domes, and hardwood hammocks forming a mosaic that would provide all their needs if treated with respect. Their traditional chickee structures—open-sided, thatched-roof dwellings raised on platforms—were perfectly adapted to this environment, allowing air circulation in the humid climate while providing protection from seasonal flooding and wildlife. Even today, tribal members maintain deep connections to the Everglades through traditions like the Green Corn Ceremony, which synchronizes with natural cycles of the ecosystem, and storytelling that passes ecological knowledge to younger generations.

Crater Lake: The Klamath Battle of Gods

The stunningly blue waters of Crater Lake in Oregon emerged from one of the most dramatic chapters in Native American mythology—a cosmic battle between gods. According to Klamath tribal traditions, the lake was formed when Llao, the spirit of the Below-World who lived within Mount Mazama, fell in love with a Klamath chief’s daughter who rejected him. In his rage, Llao emerged from the mountain to attack the Klamath people, but was confronted by Skell, the spirit of the Above-World. Their epic battle hurled fire and stones across the landscape, with Skell eventually triumphing by pushing Llao back into the mountain, which collapsed to form the caldera that would become Crater Lake. The Klamath people considered the lake a place of tremendous power where shamans would seek spiritual guidance, often at great risk given the site’s dangerous spiritual energy. The island at the center of the lake, now called Wizard Island, was believed to be where the final battle between these cosmic forces ended. For thousands of years, the Klamath forbade speaking of the lake to outsiders and approached its rim only for vision quests and specific ceremonies.

Monument Valley: The Navajo Land Between Realms

The iconic sandstone buttes of Monument Valley stand as sentinels within the Navajo Nation, where they are known as Tsé Biiʼ Ndzisgaii (“valley of the rocks”). In Navajo creation stories, these dramatic formations are much more than geological features—they represent Yei bi cheii, supernatural Holy People who were frozen in stone at the dawn of the current world. The Left and Right Mittens formations symbolize the creator deity’s hands placed upon the earth in blessing, while other formations represent mythological heroes who protect the Navajo people. Traditional hogans (Navajo homes) were oriented with their doors facing east toward the valley, allowing residents to witness the daily renewal as dawn light transformed the colors of the monuments. Many Navajo medicine people still conduct healing ceremonies in the shadow of these formations, believing they amplify spiritual energies. The valley’s distinct position at the intersection of the four sacred mountains that bound Navajo territory makes it particularly significant as a place where different spiritual realms connect, offering unique access to divine powers that maintain harmony in the universe.

The Modern Intersection of Parks and Native Heritage

Today, a significant shift is occurring in how America’s national parks acknowledge and incorporate Native American perspectives in their management and interpretation. Many parks now feature collaborative exhibits developed with tribal historians, emphasizing Indigenous names for landmarks alongside their English designations and explaining the spiritual significance of landscapes beyond their geological interest. At Grand Canyon National Park, the Desert View Watchtower area has been transformed into an Inter-tribal Cultural Heritage Site where various tribes with connections to the canyon share their distinct perspectives with visitors. Parks like Mesa Verde and Canyon de Chelly now employ Native American interpreters who can share authorized traditional knowledge while respecting boundaries around sacred information. Some parks have established formal co-management agreements with tribes, acknowledging their historical stewardship and incorporating traditional ecological knowledge into resource management decisions. These partnerships represent a growing recognition that America’s most treasured landscapes are not wilderness void of human history, but places shaped by thousands of years of Indigenous relationship and care.

Conclusion

America’s national parks preserve not only spectacular natural features but also the living heritage of Indigenous cultures that have been intimately connected to these landscapes for millennia. The legends and stories associated with these places reveal sophisticated understandings of natural processes, encode cultural values, and affirm deep spiritual connections between people and the land. As we hike through ancient forests, gaze at towering rock formations, or stand beside powerful waterfalls, we walk in landscapes made richer by the stories Native peoples have told about them across countless generations. By acknowledging and respecting these cultural dimensions of America’s most famous parks, visitors can gain a more complete appreciation of these treasured places—not just as scenic wonders, but as living libraries of America’s first stories.