National parks and tribal nations share a complex and evolving relationship that spans centuries of American history. The magnificent landscapes that visitors admire today in many national parks were once—and in many cases still are—the ancestral homelands of Native American tribes. For generations, the management of these protected areas often excluded indigenous voices and knowledge, creating tension and distrust. However, in recent decades, the National Park Service (NPS) has increasingly recognized the importance of working collaboratively with tribal nations to manage these shared spaces. This shift represents not only an acknowledgment of historical injustices but also an understanding that indigenous knowledge and perspectives are vital to effective conservation and cultural preservation.

The Historical Context of National Parks and Native Lands

The establishment of America’s national parks often came at a significant cost to indigenous peoples. When Yellowstone became the world’s first national park in 1872, it was presented as “untouched wilderness”—a characterization that erased thousands of years of Native American presence and stewardship. Many tribes were forcibly removed from their ancestral territories to create these supposedly pristine landscapes for public enjoyment. The Ahwahnechee people were displaced from Yosemite Valley, the Blackfeet from Glacier National Park lands, and numerous tribes from the Grand Canyon region. This painful history created a legacy of distrust that continues to influence relationships between tribal nations and park management today. Understanding this context is essential for appreciating the significance of contemporary collaborative efforts.

Legal Frameworks for Tribal-Park Relationships

Several key laws and policies now govern the relationship between the National Park Service and tribal nations. The National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 requires federal agencies to consult with tribes on management decisions that might affect cultural resources. The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) of 1990 addresses the return of cultural items and human remains to tribal nations. Executive Order 13175, signed in 2000, mandates meaningful consultation with tribal officials when developing federal policies with tribal implications. The 2016 NPS Management Policies further strengthen these commitments by acknowledging that many parks contain resources of cultural significance to American Indian tribes and by establishing formal consultation processes. These legal frameworks provide the foundation for government-to-government relationships between the NPS and federally recognized tribes.

Co-Management Agreements

Co-management represents one of the most progressive approaches to park-tribal relationships, where decision-making authority is formally shared between the NPS and tribal nations. Canyon de Chelly National Monument in Arizona exemplifies this model, as the NPS manages the monument while the land remains Navajo Nation property, creating a unique partnership that honors both conservation goals and indigenous sovereignty. At Grand Portage National Monument in Minnesota, the Grand Portage Band of Lake Superior Chippewa owns the land and co-manages it with the NPS through a formal agreement that recognizes their cultural and historical connections to the area. Big Cypress National Preserve in Florida involves several tribal nations, including the Miccosukee and Seminole, in management decisions, especially regarding traditional activities and cultural resources. These arrangements acknowledge that tribal nations possess both rights to and knowledge about these lands that extend far beyond conventional park management approaches.

Traditional Ecological Knowledge Integration

Indigenous peoples have developed sophisticated understanding of local ecosystems through generations of observation and interaction with their environments. This Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) offers invaluable insights into sustainable land management practices that national parks are increasingly incorporating into their conservation strategies. At Yosemite National Park, traditional burning practices of the Southern Sierra Miwuk and other tribes are informing contemporary fire management techniques, helping to restore forest health and reduce catastrophic wildfire risk. Olympic National Park collaborates with coastal tribes like the Makah and Quileute on marine resource management, drawing on their deep knowledge of ocean ecosystems. In Glacier National Park, Blackfeet knowledge about bison behavior and ecology has contributed to successful conservation efforts for this iconic species. These collaborations demonstrate how combining Western scientific approaches with indigenous knowledge can lead to more effective and culturally appropriate conservation outcomes.

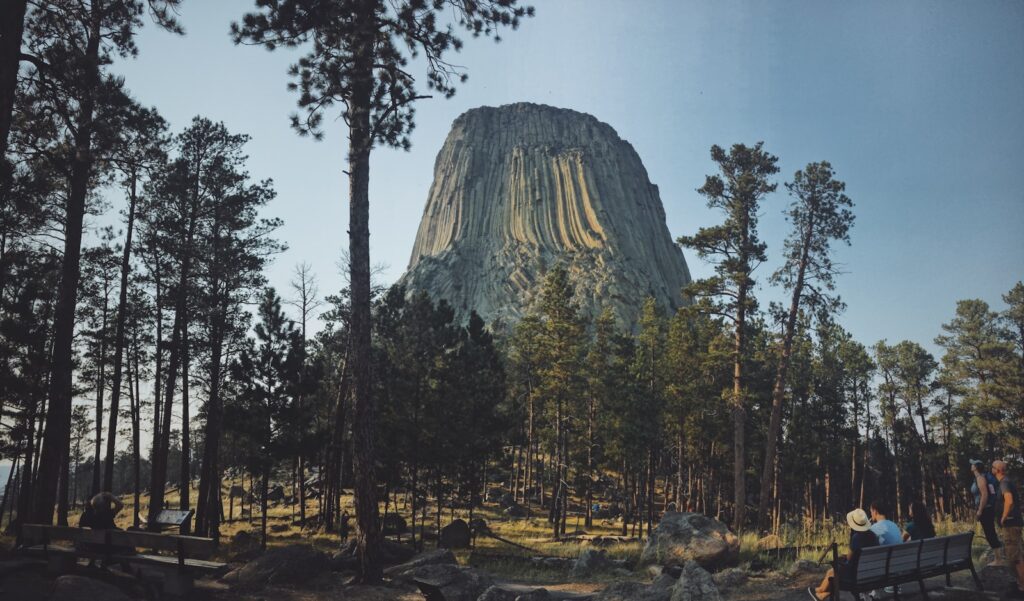

Protecting Sacred Sites and Cultural Resources

Many national parks contain places of profound spiritual significance to tribal nations, requiring special management considerations. Devils Tower National Monument (known to many tribes by traditional names such as Bears Lodge) in Wyoming has implemented a voluntary June climbing closure to respect Northern Plains tribes’ cultural ceremonies during this sacred month. At Mesa Verde National Park in Colorado, Ancestral Puebloan archaeological sites are managed with input from 26 associated tribes to ensure appropriate preservation and interpretation. Mount Rainier National Park works with several tribes including the Nisqually, Puyallup, and Yakama to protect traditional plant gathering areas and ensure access for cultural practices. These collaborative approaches recognize that cultural resources extend beyond physical artifacts to include living traditions and spiritual connections to place that remain vital to tribal identity and well-being.

Subsistence Rights and Traditional Use

Access to traditional foods and materials within park boundaries remains crucial for many tribal communities’ cultural practices and subsistence needs. In Alaska, the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) explicitly protects subsistence hunting and fishing rights for Alaska Natives within parks like Denali and Gates of the Arctic. At Grand Canyon National Park, the Havasupai Tribe maintains gathering rights for certain plants used in traditional medicine and ceremonies. Acadia National Park in Maine has worked with Wabanaki tribes to ensure access to ash trees for traditional basket making, an art form of both cultural and economic importance. These arrangements acknowledge that severing indigenous peoples’ connections to traditional resources not only violates their rights but also undermines cultural continuity that has persisted for thousands of years.

Interpretation and Education Partnerships

Collaborative approaches to visitor education are transforming how national parks present indigenous histories and perspectives. At Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument in Montana, interpretation has evolved from a one-sided narrative about “Custer’s Last Stand” to include Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho perspectives on this historic conflict. Grand Teton National Park partners with the Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho tribes to present cultural demonstrations and educational programs that highlight their continuing connection to the landscape. Mesa Verde National Park’s visitor center features exhibits developed with affiliated Puebloan tribes that center indigenous voices in telling the story of the ancestral cliff dwellings. These partnerships help create more accurate and comprehensive interpretations that acknowledge both historical injustices and the enduring presence of Native peoples, challenging the “vanishing Indian” narrative that has long dominated public understanding.

Tribal Tourism Initiatives

Economic opportunities through tourism represent an important aspect of tribal-park relationships. At Badlands National Park, the Oglala Sioux Tribe manages the South Unit through a cooperative agreement, developing their own visitor facilities and programs that provide economic benefits directly to the tribal community. Near Grand Canyon National Park, the Hualapai Tribe has developed Grand Canyon West and the famous Skywalk attraction on their own land, creating substantial tourism revenue while maintaining cultural control over how their heritage is presented. In Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park, Native Hawaiian cultural practitioners offer demonstrations and programs that both preserve traditional knowledge and provide income opportunities. These initiatives help address economic disparities while giving tribes greater agency in how their cultures are represented to the public, creating more authentic experiences for visitors while supporting tribal self-determination.

Repatriation of Cultural Items

The return of cultural artifacts, human remains, and sacred objects to tribal nations represents a crucial aspect of healing historical wounds. Under NAGPRA, parks like Mesa Verde have repatriated thousands of artifacts and human remains to descendant communities, acknowledging past wrongs in how these items were obtained and displayed. Effigy Mounds National Monument in Iowa has worked to return sacred objects and ancestral remains to tribes including the Ho-Chunk, Ioway, and others with ancestral connections to the mounds. Olympic National Park has facilitated the return of items in its collections to local tribes including the Makah, Quileute, and Lower Elwha Klallam. These repatriation efforts recognize that cultural items are not merely scientific specimens or museum curiosities but living connections to ancestral traditions that belong with their communities of origin.

Challenges in Park-Tribal Relationships

Despite progress, significant challenges remain in establishing truly equitable partnerships. Limited funding often constrains the ability of both the NPS and tribal nations to fully implement collaborative programs, with tribes particularly affected by resource constraints. Bureaucratic processes within federal agencies can move slowly, creating frustration when tribal priorities require more immediate action. Cultural differences in decision-making approaches sometimes create misunderstandings, as Western bureaucratic timelines may conflict with tribal consensus-building processes. Historical distrust stemming from past injustices continues to affect current relationships, requiring ongoing commitment to building genuine trust through action rather than words. Addressing these challenges requires sustained commitment, cultural humility, and institutional flexibility from park management, along with adequate resources to support meaningful collaboration.

Case Study: Bears Ears National Monument

Bears Ears National Monument in Utah represents one of the most innovative approaches to indigenous involvement in public lands management. The original 2016 designation came after extensive advocacy by the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition, comprising the Hopi, Zuni, Ute Mountain Ute, Uintah and Ouray Ute, and Navajo nations. The monument established a formal Tribal Commission that gives these five tribes significant input into management decisions, recognizing their deep historical and ongoing connections to this landscape containing over 100,000 archaeological sites. Though the monument boundaries were controversially reduced in 2017, the Biden administration restored them in 2021, reaffirming the tribal co-management approach. Bears Ears demonstrates both the possibilities and politics of indigenous involvement in public lands, showing how tribal leadership can drive conservation while ensuring protection of cultural resources in ways that respect living traditions.

Emerging Models of Indigenous-Led Conservation

Beyond traditional park-tribal relationships, new models of conservation led by indigenous communities are emerging. The Kootznoowoo Wilderness in Alaska’s Tongass National Forest is co-managed by the Tlingit people’s tribal corporation and the U.S. Forest Service, establishing a precedent that could influence future national park management approaches. In Montana, the Blackfeet Nation established their own Iinnii Initiative to restore bison to their traditional lands adjacent to Glacier National Park, complementing the park’s conservation efforts while maintaining tribal autonomy. The Indigenous Guardians program in Canada offers another model being studied by U.S. agencies, where First Nations receive funding to monitor and manage their traditional territories, including areas that overlap with national parks. These innovative approaches suggest a future where indigenous communities lead conservation efforts rather than simply participating in management systems designed without their input.

The Future of Park-Tribal Partnerships

Looking ahead, several trends point toward deeper and more equitable relationships between national parks and tribal nations. Climate change adaptation planning increasingly incorporates indigenous knowledge about environmental changes and resilience strategies, recognizing that tribal observations often provide insights unavailable through conventional scientific monitoring. Technological innovations like digital mapping are helping document tribal cultural landscapes across park boundaries, creating more comprehensive understandings of indigenous connections to these places. Younger generations of both park professionals and tribal members are bringing new perspectives less burdened by historical conflicts, often finding common ground in conservation goals and cultural preservation. As the conservation field increasingly recognizes that the exclusion of human relationships with landscapes has often failed both ecological and social objectives, indigenous models of human-nature relationships offer powerful alternatives for reimagining how protected areas might function in the future.

The evolution of relationships between national parks and tribal nations reflects a broader societal reckoning with America’s colonial history and a growing recognition of indigenous rights and knowledge. While significant challenges remain, the movement toward collaborative management, cultural respect, and shared decision-making authority represents an important correction to historical injustices. These partnerships not only benefit tribal communities by acknowledging their sovereignty and continuing connections to ancestral lands, but also enhance conservation outcomes by incorporating millennia of ecological knowledge. For park visitors, these collaborations offer richer, more accurate understandings of these iconic landscapes as places shaped by human relationships rather than pristine wildernesses. As this work continues, it offers hope that our national parks can become spaces of reconciliation and shared stewardship that honor both natural and cultural heritage.